by Emily Jisoo Bowles

Archive Fever, the Archival Turn, an Archival Impulse: such are the key texts and descriptors used to epitomise our fascination with archives. The terms evoke a strong unconscious desire, the way a worm might instinctively inch towards a rotting piece of fruit, ripe for transformation. In the grip of the archive, working with or against it is not a matter of choice, but a necessary intervention. At this year’s IFFR, I watched many films drawing from a range of archives—institutional and private, analogue and digital—that appropriated and misappropriated their source materials into something new. It is a process that erodes as much as it generates. In Catherine Russell’s book Archiveology, she writes that “the archival economy is predicated on a principle of loss.” The loss is not merely physical, the inevitable degradation of celluloid, but also an intangible one: the stories and memories lost to history, absent from the archive. Even within the archives, there are so many histories that are irretrievable, locked up in closed-access vaults or wayward in the bottomless chasm of the internet. In the midst of our archival chokehold, how are filmmakers using found footage practices to interrogate these losses?

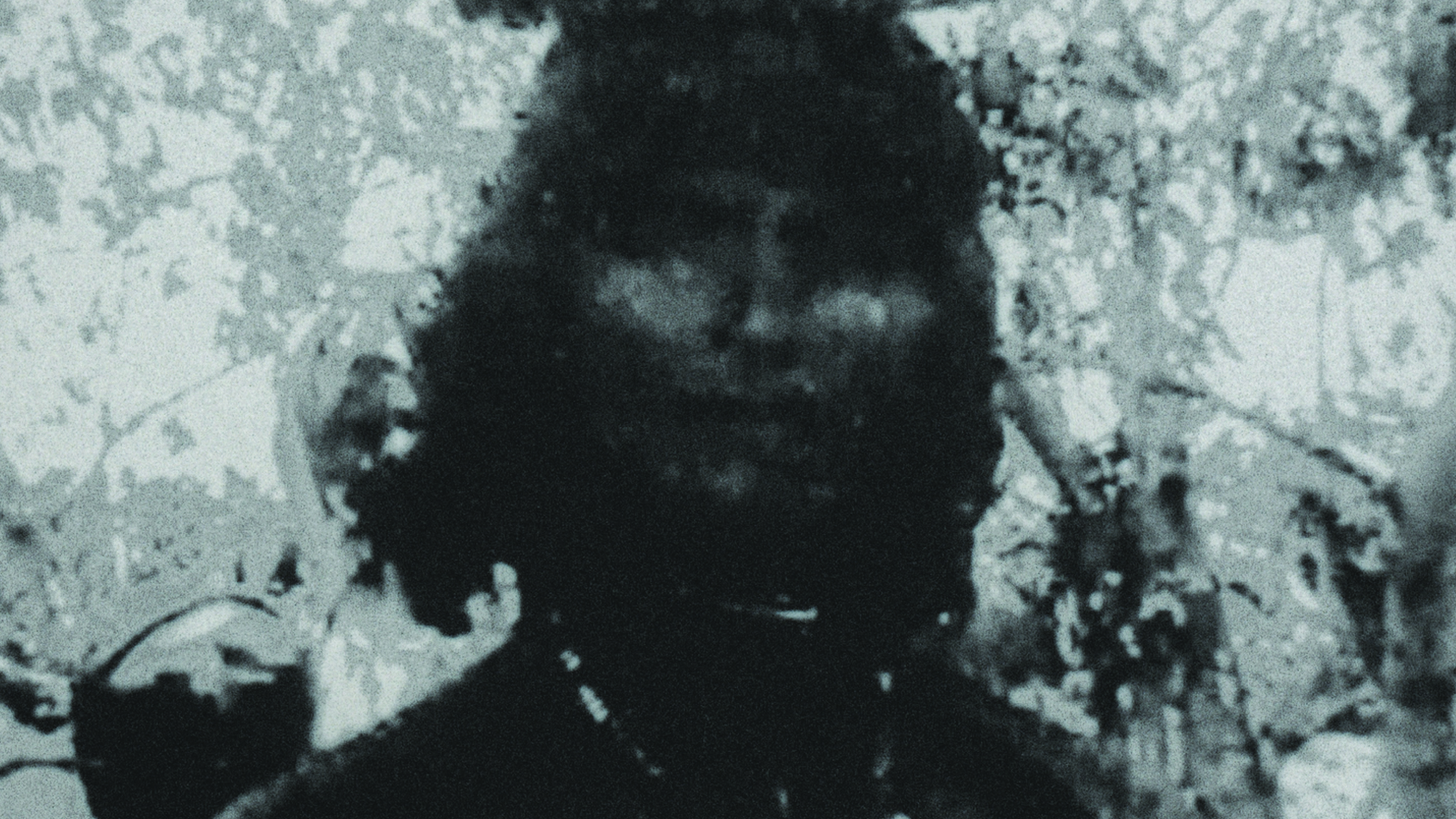

In Diana Allan’s film Partition (2025), ghosts manifest physically through the celluloid. Rephotographing the British colonial archive’s footage of Palestine from 1917-1948 on film, the differing frame rates (23 versus 24 frames per second) of the two 16 mm mediums create glitches and apparitions in the images. The Palestinians and the landscape captured by the camera are rendered opaque and unknowable, countering the colonial gaze that seeks to document, possess, and extract. Against James C. Scott’s notion of “Seeing Like a State,” which forces legibility on its subjects, the spectres in the film grain blur them into anonymity.

The silent colonial footage is accompanied by sound recordings from Allan’s project, the Nakba Archive, which gathers oral histories from Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. The voices speculate about the people in the videos: “I have no idea what he’s saying but he looks shy,” one of the participants remarks. In another clip, a boy walks into the distance, “As if someone told him: ‘just walk straight’,” she says. Their words simultaneously undermine the authority of the colonial archive and restore some sense of agency back to its subjects, yet the unknowability of the onscreen Palestinian lives persists. The opacity of the archive speaks to both the material decay of the celluloid and the loss of memories, traditions, whole cultures that have been erased by genocide. At times, the frame is frozen, rewound or zoomed in, as if searching through the images for traces or clues, only to find pixels.

If the illegibility of the images of Partition speaks to their material and figurative fragility, then the digital archives of Altyazı Cinema Association, a Turkish film collective, poses the opposite problem, namely a superabundance of footage and unfinished films. In their omnibus film Seen Unseen: An Anthology of (Auto-)Censorship (2024), six videos by different filmmakers contemplate how censorship and self-censorship shape filmmaking in Turkey. The first film of the series, Doubts by Fırat Yücel, makes visible the labour of post-production. An imaginary conversation between two filmmakers over text is superimposed over the image, as they discuss which footage of the 2013 Gezi Park protests to use in their documentary. They scroll through vast spreadsheets categorising the videos by location and content, laying bare the hours of dull admin that undergirds digital archiving. “What do we want to say about the resistance after all these years?” they ask. “The extent of the police violence? The will to claim your city?” The self-reflexive mode of desktop essay conveys the contradiction between the seemingly infinite ways to portray the protests and the self-censorship filmmakers must practice to avoid arrest. They debate whether to include footage from the public forums held in the park or people spraying graffiti onto a building. What is too incriminating to include in the film? Even as they work through the footage, the futility of that question reverberates: the filmmaker Çiğdem Mater was arrested for a documentary she didn’t even make. The mere ability to make a film is in itself an incriminating act. It’s rather through and not despite the impossibility of making a film that the practice persists.

In Missing Documentaries by Sibil Çekmen, the filmmaker compiles footage from unfinished documentaries, either partially made or not even started. Fragmented clips of bombs exploding collide with images of children collecting bullets from the street, “The Eid candies, from the police to us.” Severed from their context, the images become noise, a choir clamouring to speak. Çekmen interviews over 30 Turkish documentary makers about their latent or aborted films, listing the reasons they had to give up on their projects, but also why they persist in the face of such unabating repression. “You just want to record the moment,” one of the filmmakers says, but when she goes home and starts editing, she feels differently: “you deeply feel its pain, its depth, its marks.” The displaced images, unmoored from their films, speak to the necessarily elliptical nature of documentary making in Turkey. Rather than a flaw, the unfinishedness becomes an essential part of the documentaries’ existence and preservation.

Sometimes, archival filmmaking is a matter of convenience and low cost. Produced by the Korean Broadcasting Service (KBS), Korean Dream: The Name-jinheung Mixtape (2024) is a found footage documentary assembled from 15 films from the now defunct production company Nama-jinheung. Released between 1968-1991, the company digitised these films in an unsuccessful attempt to sell them to Netflix, and the ease of using pre-digitised footage became the primary reason that filmmaker Lee Taewoong picked them as his source material. The films themselves are unremarkable. As typical genre movies of the era, ranging from kung fu, comedy, and horror, they remain largely forgotten, excluded from the Korean film canon. By cutting and collaging them, Lee has salvaged them from the abyss of the digital trash can, like Bruce Conner did with discarded film from the bins of Hollywood in the 1950s. Lee compiles the footage into montages of the same tropes occurring throughout the films, the repetition unveiling the hegemonic ideologies of patriarchy, anti-communism, and nationalism underpinning them.

Found footage might be cheap in cost, but certainly not in meaning. Lee’s collaging produces ways of looking at Korean history that subtly subvert the dominant narratives of nation building that exist within and around the films. In the age of blockbusters dramatizing painful Korean histories like the Japanese occupation into bombastic spectacle (Exhuma (2024), Phantom (2023), too many to count), the fragmented films posit non-linear and ambivalent alternatives. The fragments retain their spectacles of melodrama and visual beauty, yet they resist immersion. A scene of a construction worker lamenting how he will never be able to afford a flat in the apartment block he helped build cuts to present day footage of the same block, now with a sign announcing its demolition and reconstruction. Faced with the constant erasure and amnesia of South Korea’s compressed modernity, found footage compilation makes visible the collective loss and trauma while refusing to succumb to the phantasmagoria.

Watching these festival selections, I think about how social media has become an archive of genocide, and the difference between seeing violence and oppression in the cinema versus on the internet. Gaza was described as the “most documented genocide in history” by the Palestinian UN representative. Since October 2023, Palestinians have been live streaming the destruction of their homes on social media, where Instagram reels of Israeli bombs are sandwiched between cat videos and craft tutorials. Despite their hyper-visibility, the personal testimonies of grief lose their affective meaning through their flattening into content, where overstimulation only breeds hopelessness and apathy. “Image culture tends to shut down historical thought but also contains the tools for its own undoing,” writes Russell. If the format of social media suppresses empathy and critical thinking, can found footage filmmaking be a tool to resist dehumanisation and desensitisation? To revive the images from the chasm of algorithms and shadowbanning to engender an engaged mode of spectatorship?

It is perhaps the very illegibility of the archive that produces an active mode of reading that goes beyond mere seeing. Whether produced by material decay or a lack of context, opacity becomes a means of reading in between the images, to situate their place in the archive, to be acutely aware of their origins and the conditions that they live in, or the information they lack. By considering archival footage as both image and document, we can understand the archive as a site of power relations. Acting as both representations of the world and historical objects, they construct the boundaries of what can be seen and said, what is known and knowable. In this way, they teach us how official narratives of history can be constructed or dismantled, as well as posit new forms of knowledge production through filmmaking.

The fragmentation of footage speaks back to the “whole” from which they were taken and recognises that they are no longer viable in their original form, whether it is because of the violence of the colonial archive, state censorship, or commercial failure. Found footage thus becomes a means of both preservation and mourning, where films and histories are remembered only in their partial and provisional reincarnations. Rather than the finality of death, archival filmmaking becomes a lifecycle where the worm-like impulse to decompose down the old detritus fertilises new life in the ecosystem of archives.

Emily Jisoo Bowles is a British-Korean film critic and programmer based in London.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting Ultra Dogme on Patreon, so that we may continue publishing writing about film + music with love + care.