by Ruairí McCann

The kiss, that flashpoint of intimacy, communication, and the present tense, has been the subject of art since its prehistory. In Andy Warhol’s Kiss (1963-64), this subject’s ancient roots, straightforward prurience, and its potential for stimulating abstraction can be found in this early example of the artist forging a new cinema: one of ground-breaking casualness and a-causality.

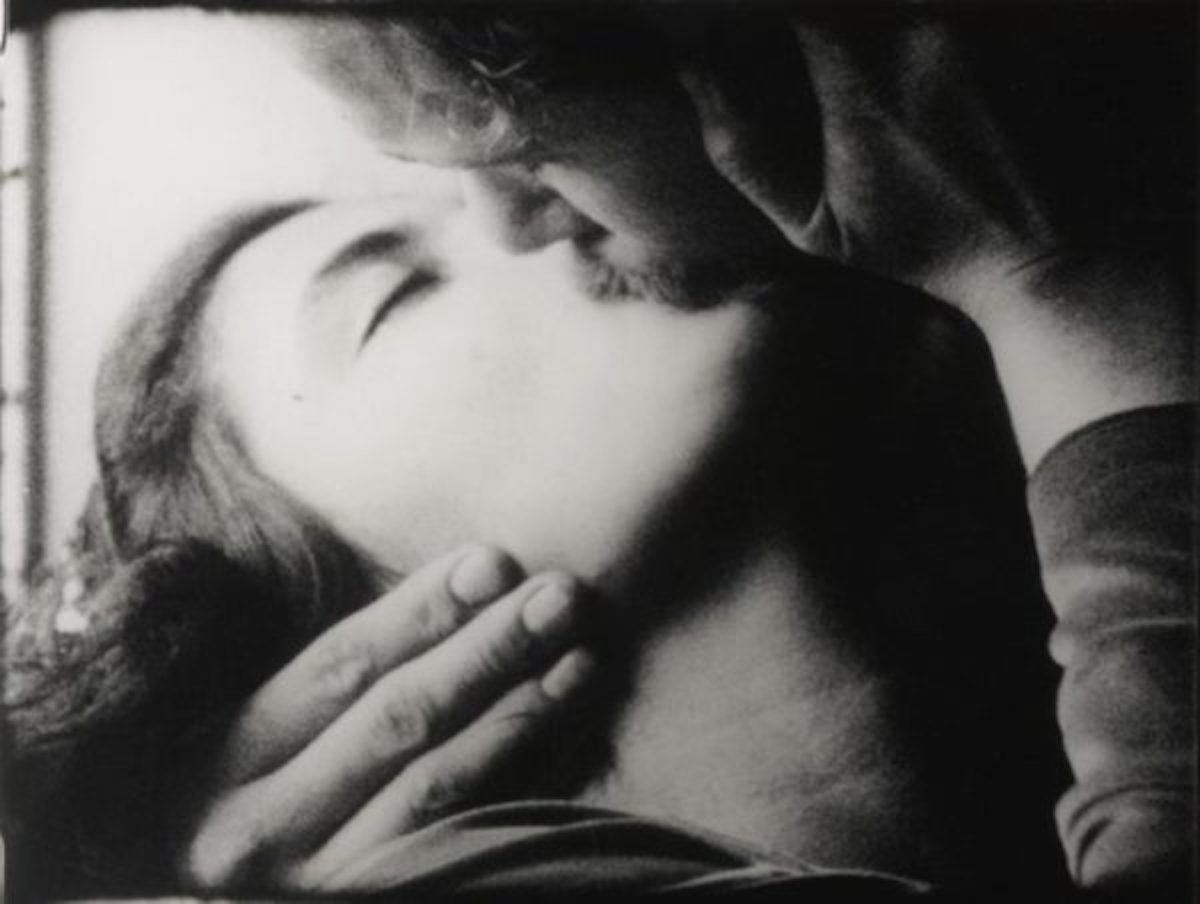

Originally conceived and screened as a serial, before being compiled in a single 50-minute-long work, Kiss consists of 13 silent close-ups, each shot on a different black & white 16mm roll and projected at the lower-than-usual speed of 16fps for between 3 and 6 minutes a pop. Each roll presents a different couple, composed of people of different races, genders and sexualities, as they make out. No context is given; we are not told who these people are (though you may recognise filmmaker Barbara Rubin, Warhol’s then assistant Gerard Malanga, pop artist Robert Indiana and superstar Baby Jane Holzer, among others) nor their actual relationship to one another. The be all and end all is the bodies on screen in intimate motion, in the moment, with the frame functioning as their kissing booth.

The latter is set to some very particular conditions; the close-ups are static and extreme with subjects’ faces regularly engulfing the screen, and only a spare stretch of background and intermittent sense of (dis)location provided by a white wall or a pitch-black room, with the occasional bit of shadow play produced by their love throes turning holographic against glaring spotlights. There are exceptions, where the camera does move and a look at the setting or the surrounding props is parcelled out. For instance, midway through couple number 4, Warhol zooms out to reveal a couch and a few hanging paintings, indicating that we are more than likely in some stratum of his Silver Factory.

It’s a rather straightforward, even rudimentary, setup, and yet it’s a film ripe for boundless extrapolation. Whole impressions, biographies and sympathies could be conjured from just homing in on the many ways each of these people kiss, from voracious to tentative, and through Warhol’s practiced inattention, his purposeful lack of purpose, and subtle manipulation of the image. For instance, the lighting during couple number 5‘s kiss is particularly high-contrast. Solid bands of silhouette wrap themselves around the pair, giving the impression of a back-alley dalliance. While with couple number 8, in which a woman is being ravished while draped across a leopard skinned settee, springs to mind a clandestine, drawing room consummation of some upper crust affair.

May Irwin & John Rice in The Kiss (1896)

Saint Suttle & Gertie Brown in Something Good – Negro Kiss (1898)

The film draws from a long history of depicting lovers in embrace in art, as above mentioned, but also in cinema. Its lineage stretches as far back as the medium’s afterbirth, with the William Heise shot, Thomas Edison produced The Kiss (1896). An actuality staged like a Warhol film, as bee-line portraiture with a similar air of passion mixed with facetiousness. Despite its frequent beauty, Warhol isn’t going for the grandness or the surface-readable subjectivity of a Klimt or a Renoir. Instead, Kiss has the directness of those cinema’s early days, or a Punch and Judy show, though with the couple’s violence subdued by attraction and replaced with a minimalism that can incite the viewer into the fits of mental maximalism.

Kiss was one of the first products of Warhol’s turn to cinema. A great burst of activity, or furtive non-activity, that straddled the mid-60s and lasted until 1968. In the aftermath of his shooting, which led to extensive surgery and a spell on death’s door, Warhol would secede most of his (complexly tenuous) hold on filmmaking to then partner Paul Morrissey. From then on, when it came to cinema and other ventures, he mostly occupied the role of ‘business artist’. The arch-overseer, icon and bankroller whose name would upholster a project and be stamped on the poster above the title.

Unlike the conceptual behemoths that would follow soon after, such as Sleep and Empire (both 1964), Kiss and its hive of romances, along with the first salvos of his Screen Tests project, would mark the start of a steady trickle of narrative and character, filtering through what Annette Michelson called a “cinema of literal textuality”. The culmination of this change, which included the employment of sound and more dynamic editing and camera movement, being that deluge of personality and chatter; the 210 minute (approximately), split-screen Chelsea Girls (1966).

The progenitor of such a major work can be found with this film, in a more direct and palliative form, lodged between locked lips.

Ruairí McCann is an Irish writer and musician, Belfast born and based but raised in Sligo. He sits on the board of the Spilt Milk Music & Arts Festival and has written for Photogénie, Electric Ghost, Screen Slate, Mubi Notebook and Sight & Sound. [Twitter]

One thought on “‘Kiss’”