The series A RISKY LIFE: LETTERS FROM JEAN-CLAUDE ROUSSEAU, curated by Edward McCarry (with special thanks to Carlos Saldaña and Hannah Yang) plays at Anthology Film Archive June 26 – June 30

by Avalyn Wu

For Jean-Claude Rousseau, it all begins with the image: its contingencies, spontaneity, and unpredictability. His methodology does not permit the premeditated, a sense of authorial domination imposed upon the world before his camera. In a 2006 interview with Cyril Neyrat at that year’s FIDMarseille, Rousseau claimed that “a film becomes gripping when you experience the director stepping aside for reality…the art of the image is about the risk of abandonment or disappearance. It’s Cézanne: with every brushstroke, I risk my life.”1 He again invoked this same Cézanne quote in a 2019 interview with Salvador Amores, saying, “Images are found, they cannot be looked for…I don’t seek, I find. It’s not comfortable. Bresson liked to cite the beautiful words of Cézanne: ‘in each stroke I risk my life.’ There should be no comfort.”2 To risk one’s life as an artist, then, is not a literal sacrifice through death. Rather, it is an act of relinquishment, the giving up of one’s ego and individuality. In the world of Rousseau, there is no place for delusions of power and control.

Taking Rousseau’s words at face value would suggest a kind of monism in his work, perhaps even an anti-dialectical sensibility. His position as a filmmaker is not to stand removed from the world but to dissolve into it, to let it take him wherever it wants. The film he eventually constructs is thus an emanation from the patterns of light and movement that nature grants him. Following this logic, he is reduced to being less than a conduit, which still maintains some kind of independent form. More extremely, he perceives his very existence as an artist to be contingent upon the suggestions of an external reality. There is no contradiction to be found, at least on this level, when subject and style are essentially one and the same.

One could chart the trajectory of his five Super 8 films as a continuous deepening of this principle. Jeune femme à sa fenêtre lisant une lettre (1983) and Venise n’existe pas (1984) remain entirely indoors, the outside world a mere image captured through the frame of a window and, in the latter case, a blurry illustration that slowly comes into focus. Keep in Touch is the transition point, with the camera leaving Rousseau’s secluded room for the first time. However, interior and exterior realms are still confined to their own shots, separated by Rousseau’s characteristic film leaders, which take the place of conventional editing. It isn’t until Les antiquités de Rome and La Vallée close, his first two feature films, that he starts to create a more dynamic interplay between his personal space and the larger environment surrounding him.

In some ways, this trajectory mirrors that of Cézanne’s. John Berger identified a “black box” within his art, the starting point for all that is substantial. This question of what exactly constituted the substantial was a driving force behind Cézanne’s evolution as an artist. In the earliest phase of his career, he reduced the substantial to the corporeal, a focus on the human body and its flesh. Eventually, he expanded his understanding to include objects that we don’t normally think of as having a body, like the fruits in his still life paintings, before arriving at his final phase, where he discovered “a complementarity between the equilibrium of the body and the inevitability of landscape.”3 To use Cézanne’s own quote, “‘The landscape,’ he said, ‘thinks itself in me, and I am its consciousness.’”4 The thought generated by the visual presence of the landscape finds physical rearticulation in a person. The autonomy of the subject and the style of the artist function as two different aspects of the same phenomenon.

Nikolaj Lübecker, drawing on Gilbert Simondon’s concept of the individus-milieux, makes a similar claim about Rousseau’s La Vallée close (1995) and its understanding of the image, saying that “by seeing and filming – by imagining – we become entangled in the texture of this world, and thereby reinvent both ourselves and the world. Or more precisely: we discover that we were always already caught up in the texture of the world.”5 Importantly, there’s less passivity in the language here. Not only are we concomitant with the world, we are also in a constant dialectical relation of change with it. In this manner, the person filming maintains an active role in the dynamic, one that is perhaps closer to how we traditionally conceptualize an artist or film director.

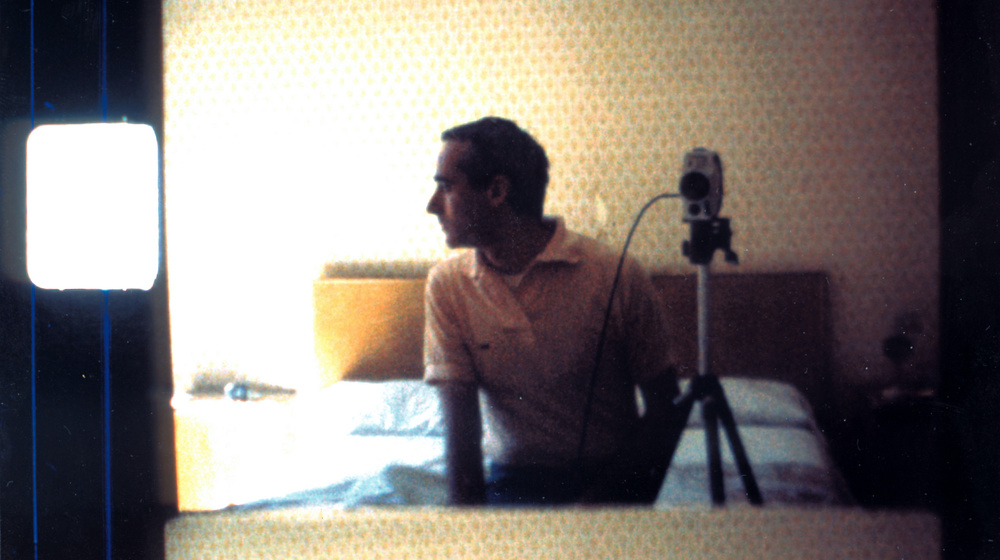

It calls to mind a moment that occurs towards the end of La Vallée close. The camera begins in extreme close-up, fixating on the crevices and shadows of a mysterious photograph. “Here is a landscape…Here is a landscape…” Rousseau intonates in the voiceover. He gives us more and more details about railroads and houses, until a cut brings us to a wider shot and he says, “You can make a map of a town, several towns, or even of the entire earth.” It is the earth of folds and wrinkles in bedsheets, used and barren, with shadows and crevices like those found in the photograph, which has now been subsumed into this larger image. And then the reel concludes as it starts, “Here is a landscape…Here is a landscape,” except the camera is in an entirely new position. It has revealed itself in shadow right next to its author, bracketed off by abnormal patches of searing light. Rousseau and the tool of his craft are now, quite literally, the landscape. All oppositions have reconciled into one—intimate and cosmic, formal and substantive, beginning and end. We return to the map that bookends Jeune femme, now a part of the fabric of everything that graces Rousseau’s celluloid. The individual-milieu of Rousseau expands through circularity and reconciliation.

Can it really be so simple? I doubt Rousseau would want his work to be so cleanly interpreted, to trail so neatly one train of thought. T. J. Clark, questioning the idea that Cézanne ever made such remarks about the landscape thinking itself in him, imagines what Samuel Beckett would retort with: “The landscape thinks itself in me! Hiker’s sentimentality! The landscape un-thinks me in it.”6 In other words, we should not take the materiality of what we see as something immediately familiar and self-evident. A fundamental enigma remains at the center of how we perceive and relate to the world. As Karl Marx said of our commodities, their value “is the very opposite of the coarse materiality of their substance, not an atom of matter enters into its composition. Turn and examine a single commodity, by itself, as we will, [Could we even say, ‘Fold and examine it?’] yet in so far as it remains an object of value, it seems impossible to grasp it.”7 Relating this enigma back to Cézanne, Clark asks, despite a certain vividness being present in his art, “isn’t what a Cézanne suggests to us most powerfully precisely the idea that vividness and immediacy may be one thing, but material existence – ‘Naturstoff, Warenkörper’ – another?”8 So we must resist another type of comfort, the comfort of self-justifying appearances. The assumption that filmed surfaces can necessarily refract us into some transcendent grasp of the material relations of the world is a faulty one. At worst, it serves as an obfuscation, a charming game of mystic aestheticism.

As much as Rousseau insists that his films are works of raccord, there is much to be said about how discord and isolation also function as core structuring elements, occasionally in ways that overlap with what Clark identifies in Cézanne’s paintings. Keep in Touch (1987)’s established alternating pattern of interior and exterior shots is broken by a rather haunting shot of people skating at night. The lighting gives the shot a vignette quality, with the bottom half of the frame entirely consumed by the dark. It’s not unlike the tipping table in Apples and Milk Jug, which makes “the emptiness of the painting’s foreground – the un-crossable gap there between me and the object-world portrayed, the imagined hard transparency of the picture plane – emerge as a thing in itself.”9 Rousseau has conjured a void between himself and other people, the sharp breaks of the film leaders bleeding into the frames themselves.

He repeats this approach to constructing foregrounds several times in Les antiquités de Rome (1991), most noticeably during the Arch of Constantine segment, where the monument is pushed way back by a vast negative space that seems traversable to everyone except Rousseau himself. In the immediate next shot, he is looking longingly out of his window, surrounded again by total darkness, before turning to look right into the lens. Suddenly, we realize that we are seeing his reflection and that he is in fact much closer to the camera than initially presumed. The relations between foreground and background are confused. Even the mixing of the sound places outdoor chatter right in the room with Rousseau. If Cézanne’s paintings demonstrate that “foreground and background are potentially crutches for the mind, which painting should put in question,” then Rousseau’s films do the same for cinema.10

Is this to say that the materialist impulse in Rousseau’s Super 8 films is a false one? Not at all. If anything, it reveals the important distinction between an actual materialist science and vulgar positivism. As valuable as the sense-data of the world is on its own, it should not serve as an excuse to terminate thought. I return to the second quote that Berger attributes to Cézanne: “Color is the place where our brain and the universe meet.”11 It’s a much more rigorous articulation of the monism of materialism, which entails not an ego death through the universe but an understanding that the existence of ideas themselves, as prompted by the objects of the world, has material expression in chemicals and other physical properties. As Nicolas D. Villareal puts it so eloquently,

Ideas that cannot in some way be encoded in a material substrate simply do not exist. They will never be available to human knowledge because they are, as far as we are concerned, not real. It is no coincidence that the invention of tools to encode things in material substrates has greatly expanded human knowledge, whether it is the drawing compass, money, paper, or computers. These things have fundamentally altered the human soul, for the human soul is a set of representations encoded in material things, and these things have grown those sets of representations by expanding the material limits of possibility.12

And one of those very material substrates is, of course, a strip of film. To see the leader in a Rousseau film thus takes on a new quality. It reminds us of the process by which all ideas become possible, by which our souls are expanded and enriched, even if this emerges paradoxically through a starker understanding of our alienation. It is that stunning driving shot near the end of La Vallée close, one of the few mobile shots in the entire film, plunging deeper and deeper into the trees. The risk is to accept that no unities are achieved easily, that the forces and relations of the world are still a mystery awaiting our curiosity.

Avalyn Wu is a filmmaker and writer based in New York City. [Twitter][Letterboxd]

If you enjoyed this article, please consider tipping the author and/or supporting Ultra Dogme on Patreon, so that we may continue publishing writing about film + music with love + care.

FOOTNOTES:

- Cyril Neyrat, “Jean-Claude Rousseau.” ↩︎

- Salvador Amores, “Our Only Hope Lies in the Image: A Conversation with Jean-Claude Rousseau.” ↩︎

- John Berger, Portraits: John Berger on Artists, 265. ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Nikolaj Lübecker, “The Individual as Environment,” 203. ↩︎

- T. J. Clark, If These Apples Should Fall, 98. ↩︎

- Ibid, 95. ↩︎

- Ibid, 100. ↩︎

- Ibid, 79. ↩︎

- Ibid, 124. ↩︎

- Berger, 265. ↩︎

- Nicolas D. Villareal, “What is Materialism?” ↩︎