As a special promotion, this month’s Movie Club (Two Films by Chantal Partamian) includes a bonus second run of ‘Roadfilm’ and ‘Raindance’ by Standish Lawder (from January’s program). Both programs are currently available to stream through this Friday, February 28th, 2025. Sign-up for the Movie Club to access both programs instantly.

by Ruairí McCann

The film historian Tom Gunning has cautioned using ‘primitive’ to describe cinema’s early years. There is not only blatant condescension bound up in the word, but the trap of circular reasoning; a faulty assumption that the forms and structures (artistic, social and economic) that make up cinema today were fait accompli and cinema’s earliest inventions and styles were destined to be rendered obsolete or else fuel for the generation of these future ‘superior’ incarnations.

The filmmaker and scholar Standish Lawder would concur. In a lecture at the Carnegie Museum of Art in 1975, he described the medium’s first few years at the turn of the century not as some slow-burnishing start, but a period where there were only “experimental films”. Since this was a new art form with no prior tradition, there was little received wisdom on how a film could be composed, and so a litany of different kinds of films, rife with possibility, flowed forth.

Lawder would mine this interest in early cinema not just through his pedagogy but also directly in his work as a film artist. Raindance (1972), one of the last films in his short period as an active filmmaker, is an ode to filmmaking as a medium of ceaseless potential. How through simple means, a single image can expand in all directions into a cornucopia of light, sound and transformation.

Like many of his films, the starting point is a short, looped piece of ‘found footage’. In this case, it’s a scene from the 1956 animated film, History of the Cinema. Despite its sober title, the film is not an account of the medium as a progressive path of advancing technical and artistic achievement, where the onrushing future devours and obliterates the past. Instead, it’s history as farce; a series of events where the lust for filmmaking is tempered, spurred or stalled by less than glamourous practicalities, marketing gambits and blunders, culminating in the contemporary craze for super widescreen exhibition. This engorging of the screen is heralded not with a chariot race or a stunning vista, but an evergreen chunk of slapstick: a man walking while reading a newspaper goes from one end of the cavernous void to the other, where he falls down a hole. It ends with a cheeky speculation on the medium’s future, a smorgasbord of new screen shapes beginning with an ouroboros, or rather something that looks a lot like one of cinema’s antecedents: the zoetrope.

Lawder chops and screws a section depicting the American film industry’s ‘discovery’ of Hollywood. This landmark event is sometimes painted as analogous to America’s larger ‘westward expansion’, as a wave of entrepreneurial filmmakers set out west to escape New York with its oppressively unpredictable weather and unshakeable monopolies on camera equipment patents. After a long journey, they find themselves in the promised land, or the perpetually bright and clear skies and plains of Southern California.

The moment is marked with the creation of a typical scene. An energetic cameraman directs two indigenous Americans. He makes them daub on warpaint and a fierce, animalistic mien before performing a ritualistic dance. The cameraman starts filming but then a sudden rainstorm, summoned by the dance and represented with a screen wipe and a pattern of white diagonal lines on black, washes him and the image away.

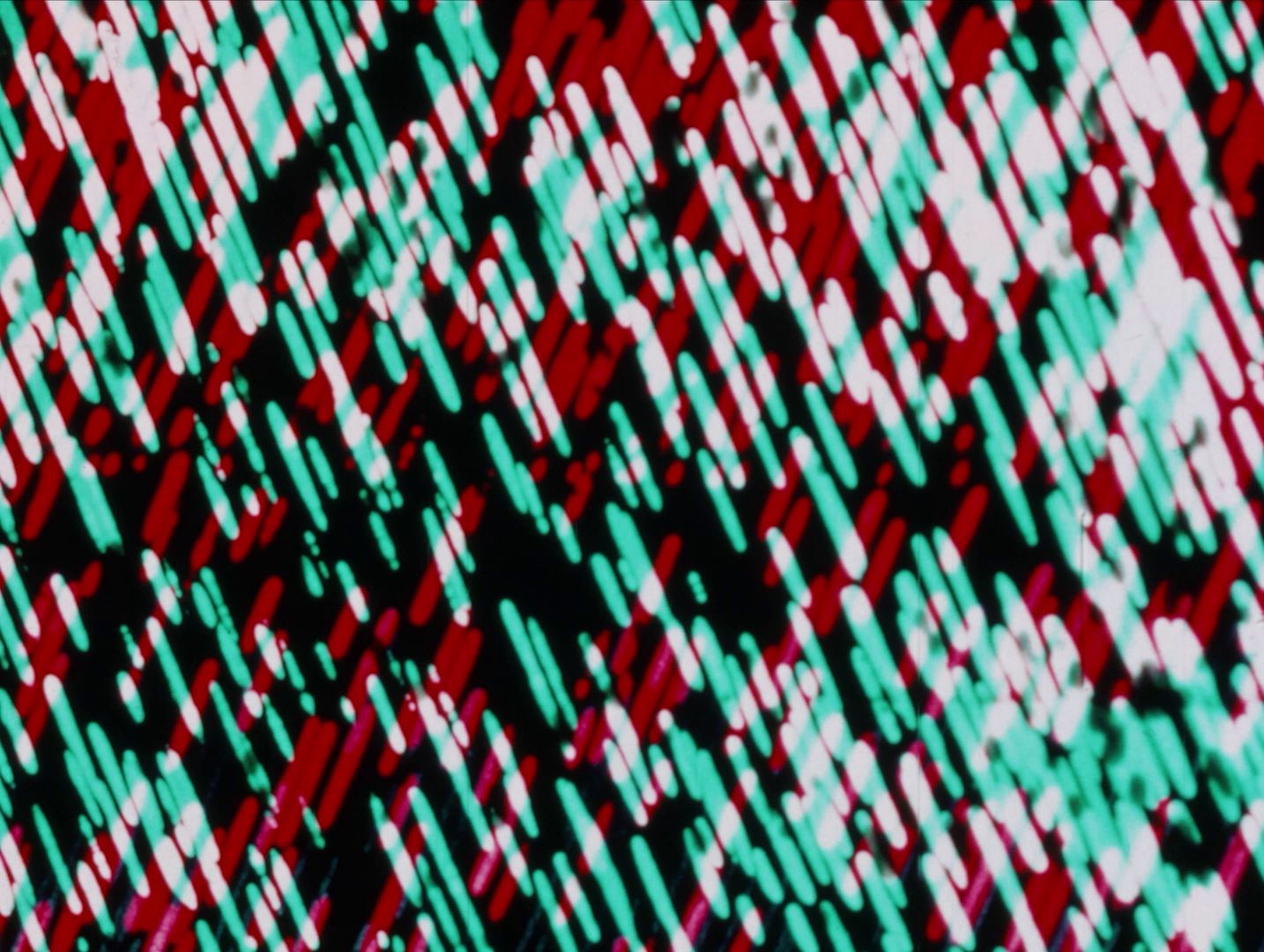

It is with this cleansing rain; this puckish uprooting of Hollywood’s cornerstone—a racist, stereotypical scene—by the abstract image, that Lawder actively sculpts his film. He takes the few seconds long interval and makes it the all-encompassing central event by repeating, manipulating, rearranging and expanding it into a flicker film of dizzying and profoundly cosmic proportions.

Using a contact printer of his own design and making, Lawder rephotographs and so alters. He mirrors and duplicates the image, flipping the sharp, little raindrops around and against each other, and then adjusts the lighting, making them dim, bulge, blot and blaze. He plays with the colours too, cycling through various tints, making it stereoscopic and eventually layering on so many duplicates and effects that the original image has become unrecognisable. Eventually returning to the original composition.

The film’s music, sourced not from the original animation but freshly composed by Lawder’s then student, and later filmmaker in his own right, Robert Withers, undergoes a parallel and bolstering journey of transformation. With its glistening, overdubbed lines of electric organ and repeating swirls of ornamentation that recall Indian classical music, it is likely influenced by Terry Riley, whose A Rainbow in Curved Air (1967) was previously used by Lawder in Corridor (1970). Like in that film, the music moves in parallel with the images, bolstering its hypnotic effect. Its initially fury of bright, arpeggiated notes fall like so many raindrops but later, as the image becomes denser and more distorted and the pace of the flicker slows, the tones become more sustained, eventually descending into a barrage of ominous glissandos.

Lawder has sometimes been thrown in with the so-called ‘structural film’ movement. There are certainly commonalities, for filmmakers such as Hollis Frampton and Michael Snow were Lawder’s contemporaries and there’s the link to the academy in his role as an art historian and an early advocate for film studies as a distinct and serious discipline. More substantially, there is the emphasis on film as film, in deriving meaning not through masking but exposing and pushing the limits of the medium itself.

And yet Raindance seems to stem out of much older roots. Namely, the abstract cinema of the 1920s about which Lawder studied, taught and wrote at length. In his book The Cubist Cinema (published in 1975, expanding on his original thesis), Lawder elaborates on how painters Viking Eggeling and Ferdinand Leger found their exploration of new possible geometric shapes, patterns and combinations reach an endpoint in painting and illustration which they then felt they could take up in the young medium of cinema. Eggeling, for instance, found that the long, tapestry-like ‘picture rolls’ he had been creating to explore new ideas could not only be replicated but furthered, into new degrees of space, time and experiential possibilities, through the long, tapestry-like film strip. It’s this insight which led to a pivotal film like Symphonie Diagonale (1924).

Lawder, too, is creating in this vein but from a more daringly simple starting point. He takes a single elemental image, in the literal and figurative sense, and while never leaving that image, draws from it an overflow of dazzling arrangements and contortions of light, on par with the wonders glimpsed when we close our eyes or look far out into space. It is a film of how the art of film and seeing can be both ionised and elaborate. How with just a few ingredients and the catalysing spark of the imagination meeting the material, a vast universe of light and motion can be constructed, unveiled, scrambled and remade again and anew.

Ruairí McCann is an Irish writer, curator, illustrator and musician, Belfast born and based but raised in Sligo. He has contributed to various publications, such as photogénie, aemi online, Screen Slate, MUBI Notebook, Documentary Magazine, Film Hub NI and Sight & Sound. [Twitter]

If you enjoyed this article, please consider tipping the author and/or supporting Ultra Dogme on Patreon, so that we may continue publishing writing about film + music with love + care.