The publication of this interview marks the beginning of a two-week stream (March 14th-28th) of SCRAP VESSEL available to Movie Club subscribers.

by Stephen Jeffrey Cappel

More incomplete dream journal than straightforward ethnography or travelogue, Jason Byrne’s Scrap Vessel (2009) is both akin to the greats of the sparsely populated—but very real—subgenre of experimental films about big boats, and truly singular as a disorienting work of gothic maritime. You may find yourself fearing, loving, and mourning a 32-year-old coal freighter as a skeleton crew of Indian seafarers shepherd it on a week long passage across the Andaman Sea to the site of its thorough dismemberment and alchemical transmogrification into rebar in Chittachong, Bangladesh.

The obvious comparison is the late landscape filmmaker Peter Hutton’s seminal At Sea (2007). Also contained within an hour and shot on 16mm, Hutton’s film tracks the life cycle of a container vessel from its construction in a South Korean shipyard to its graveyard in Bangladesh. To dismiss Byrne’s film as copy-cat based on description alone would be a mistake, however. While completed two years after At Sea, Byrne’s shoot for Scrap Vessel began over three years prior to the release of Hutton’s film. What Byrne has sculpted in his film is an altogether different achievement, a personalized and fragmentary account of an obsession-driven, half-remembered adventure set to an ambient score caught between serine and eerie, organic and synthetic.

While Scrap Vessel opens adrift, At Sea begins on the stable resting point of the port. Similarly, these interzones of mechanized labor offer geographical orientation and narrative punctuation along the epic oceanic journeys seen in other idiosyncratic maritime shipping docs such as Dead Slow Ahead (Mauro Herce, 2015), and five times throughout the 37-day runtime of the post-Warhol Logistics (Erika Magnusson and Daniel Andersson, 2012). In comparison, it is significant that Scrap Vessel is a boat movie without a port. The first of several pithy intertitle sections from Byrne’s perspective explain that Hari Funafuti (formerly the Hupohai for its Chinese crew, and Bulk Promotoer for the Norwegian denizens before them) has already left from the coast of Singapore. Its last port of service, Shanghai, is not mentioned.

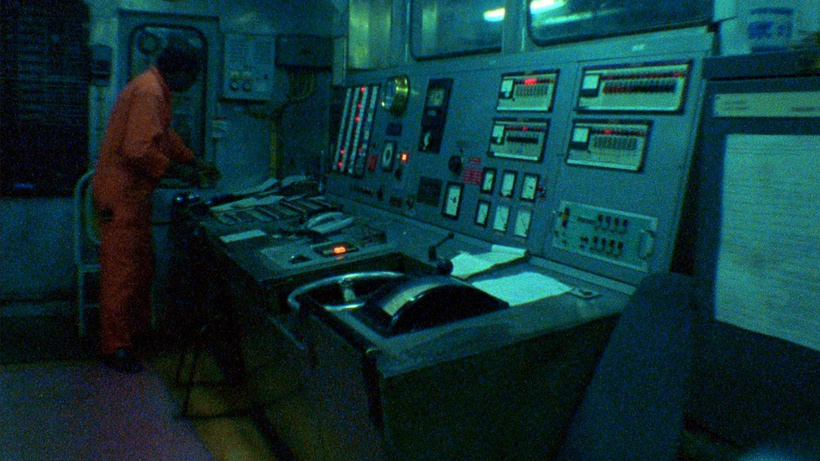

The immediate placement on the sea through a perpendicular angle peering seven-stories above the swells below and a transition into shimmering industrial hallways lined with churning, unrecognizable machinery conveys an almost instantaneous sense of gritty unreality. All of Byrne’s images travel through the dense substance of the film’s own emulsion. Holes, scratches, and voluptuous, hypnotizing grain let the images bubble up as deep blacks, dark blues, and as aptly described in Matt Sussman’s review of the film in 2010, “the occasional brilliant flash of chartreuse.” As At Sea ventures from the Lego Land order of a container port to the grime of the ship breaking yards, the medium capturing these images is left far more pristine. Watching Scrap Vessel comes with the sensation of being submerged in an oily fluid.

It does not take long for the film’s dense mood to make further forays into the conventions of gothic literature. Scrap Vessel is Edgar Allan Poe, whereas At Sea is the Hudson River School. The past lives of its former Chinese crew are unearthed through cassettes, vacation photos, and over a dozen cases of 16mm propaganda films. As one cassette unwinds, Albert Ortega’s electronic score of modulated drones and chimes is substituted with a soaring orchestra. The powerful plumes the vessel creates in its plow against the ocean no longer bears the cloudy aura of an ominous dread, but the freedom, excitement, and melancholy of a shared life at sea that no one currently aboard can fully inhabit. Byrne, aware he is among the ghosts in someone else’s boat, places both the archival footage and his own within the same continuity of mortal, fallible memories. Like Hari Funafuti’s remains in the re-rolling mills of Chittachong, the spliced material of Scrap Vessel forms its own arrow coil of shimmering light. Through years of slow re-edits, photographing and re-photographing, winding and unwinding, the film is a serpent of scintillating atoms on the cusp of losing all resemblance of what it once was.

Scrap Vessel’s haunting atmosphere never becomes too oppressive thanks to the presence of the Indian crew, hired on for their lack of personal attachment to Hari Funafuti. Often caught in friendly and upbeat gestures, they make for welcoming Charons for a beloved, rusted monster, rendered obsolete by an expanding global industry uninterested in romance. More of these friendly moments occur once off the coast of Chittachong, where the vessel is anchored and waits for five days while hollowed-out metal corpses are visible along the shoreline. The Bangladesh navy visits to buy off valuable equipment, New Year’s is celebrated among the crew, a piracy attempt is thwarted (followed by a playful re-staging for the camera). Captured through a five-minute take on a fixed tripod atop the bridge as it begins to aggressively rattle, the ship then collides into the beach with no hope of touching the open sea ever again.

The fruit of Byrne’s first 9 laborious years into filmmaking, Scrap Vessel had about as auspicious a first few years as a mid-length experimental documentary could ask for. While visiting a training site for Gambian pouched rats to sniff out landmines in Mozambique, Byrne received word from producer Mike Plante to check his emails, where he found that his film was accepted into the 2009 New York Film Festival’s Views from the Avant-Garde sidebar. Placed in a screening block alongside Harun Farocki’s In Comparison, Byrne’s film garnered praise from Jem Cohen and received a positive bump from Manohla Dargis in her coverage of the festival. 2010 saw the film curated in the 28th edition of the San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival and Byrne’s inclusion in Filmmaker Magazine’s “25 New Faces of Independent Film.” The film won best documentary in the Black Maria Film Festival’s touring program, played at the Los Angeles Film Forum through archivist Mark Toscano, and earned the admiration of Allan Sekula (who made the containerization essay film Forgotten Space with Noël Burch) and Peter Hutton, who described it to Plante as “a very complicated found object.”

Despite the acclaim of peers and requisite accolades, Scrap Vessel 15 years on has somehow become more of an obscure enigma than a household name of avant-doc film culture. Apart from write-ups from its major festival screening and a Blogspot site containing some ephemeral curios, little information is readily available about the film’s production and the man who made it.

Jason Byrne is an archivist whose 25 years in the field has come with postings at the UCLA Film & Television Archive, Academy Film Archive, and the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda in Tanzania—a gig he secured while scrambling to finish post-production on Scrap Vessel in 2008 and the kernel for one of several long-gestating projects for which this article regrettably has scarce room to describe. Today, he is an archivist at the Black Film Center & Archive in Bloomington, Indiana, where he has been processing and digitizing the collection of Senegalese-born African cinema pioneer Paulin Soumanou Vieyra.

Byrne attributes his interests in the shipping world and industrial macabre to his childhood in the alpine landscape of Sonora, California. The accident-prone nature of the town’s lumber industry kept Byrne’s father busy as an orthopedic surgeon. When the occasional derailment along an infamous hairpin turn on the tracks would cut him off from work, the elder Byrne would pick up his children early from elementary school and take them to the site of toppled detritus. Having grown up on VHS horror movies and binging Takeshi Kitano films on Mike Plante’s couch while attending the University of Arizona, Byrne developed a deep interest in cinema but didn’t care to be a filmmaker. After finding a comfortable fit in archival work interning and subsequently joining the Academy Film Archive, that assumption changed. The more Byrne reeled through films, the more he became interested in reeling through his own.

In late September 2001, Byrne took a two week vacation from his job at the Academy and booked the first available flight to Paris following 9/11. Byrne’s meticulously planned trip staggered when he woke up one morning and realized he had nothing on his itinerary. On a whim, he took a train to Marseilles with hopes of shooting the container ports on his Super 8 camera. After two failed attempts to convince port guards to let him enter, Byrne later snuck in through the entrance while workers left for their lunch break. The resulting roll of film is a dilating time lapse that captures a container ship’s loading and unloading. Byrne had hoped to capture the vessel’s gradual rise and fall in the water, unaware at the time that boxships and the transferal of their containers were perfected to keep a ship balanced as cargo was taken out as quickly as it was received. What later struck Byrne with his footage was the dance of orange-yellow forklifts and other vehicles that popped like bright caterpillars on the film stock.

About a year later, the final inception that set Byrne on course with Scrap Vessel came at a library book sale while visiting his mom in Monterey, California. A children’s color picture book entitled Super Cargo Ships caught Byrne’s attention. In love with the Kodachrome-like vividness of the book’s simple presentation of various behemoth freighter ships, Byrne was struck upon reaching its final pages.

On the left side, it just said, “Where Old Ships Go to Die.” On the right side, it was this picture of a ship that was vertically chopped in half on the front and it was awkwardly leaning to the side on this beach. To me it was such a violent image. It made me think of some future world where mechanical beached whales existed. It was almost horrifying looking at that, and it drove me into figuring how to get access to the ships. I didn’t know about any other moving images that showed these places. Working with film and also working with some ships that are being retired, most likely 30 plus years old, it seemed like these two things are kind of blended into one another.

Byrne later made contact with a Gujarati man living in Maryland, who served as a middleman between shipowners and ship breakers. With potential access to ship breaking yards, Byrne sent the roll of film shot in Marseilles as his submission to CalArts with the hope of using the resources provided by his education to make the film. Two years later, he was at sea. It would take four more years before he had a work he felt comfortable showing.

I first spoke with Byrne over a video call on July 13th of this year, following a screening of Scrap Vessel at the collective-run micro-cinema Spectacle, in Brooklyn, NY. I included the film in a series the theater put together that was trying to make a case for that aforementioned sub-category of experimental movies about big boats. Unbeknownst to me, this was the first time Scrap Vessel had screened in New York in almost 15 years. Unbeknownst to Byrne and I, the audible shuffling and murmurs that grew over the course of our talk had less to do with the dozen-or-so audience members growing tired of the discussion but were reactions to breaking news of what appeared to be an assassination attempt on a presidential candidate at a campaign rally.

Byrne spoke with me again in mid-November, as months of sitting on unanswered questions and knowing almost no substantial writing on the film existed finally wore on me. Both of us in a post-election haze, we talked for 3 hours to try to fill in the remaining gaps in the first account I received from Byrne. Many gaps still remain.

This text only accounts for some of what Byrne has been generous enough to share with me regarding the making of Scrap Vessel. The transcripts of our conversations and snippets from our email correspondences have been reduced, combined, and edited for clarity.

Stephen Jeffrey Cappel: How did you get from the inspiration to make this film to finding yourself on a ship bound for Bangladesh? Did you have any say in choosing the boat you were going to get, or did you have to take whatever your middleman ended up finding for you?

Jason Byrne: I just assumed it would be impossible to get on a ship. So initially I was just gonna go to the ship breaking yards in India and film as much as I can about demolition and cutting and try to talk to people, and just try to get a sense of what that world was.

So I went to Gujarat, and I just had a really difficult time getting into the yards because there happened to be a huge French aircraft carrier that was called Clemenceau coming from Marseilles. It was actually going to go there and beach but the problem was that it had like hundreds of tons of asbestos in it. So it’s kind of a nightmare because anybody who’s clearly not from there is seen as Greenpeace. I just couldn’t get the access.

There is some footage in Scrap Vessel from Alang [Ship Breaking Yard], and that’s video that I reverse telecined. That was totally snuck footage. I shot that maybe like a month before getting on the ship.

Then the middleman, the guy who hooked me up with everything, told me, “Maybe you can get on one of these freighter ships and actually take the ship in. Then they can’t really do anything once you’re beaching, right?”

“Yeah, that’s actually really what I want to do.”

I found out about the ship about a week before it left Singapore. I was in India and I flew my friend Theron Patterson who was in Istanbul, to do sound. Luckily somebody from CalArts that we knew, a Singaporean woman, was actually home, and so we stayed with her for five days waiting for the ship to take off.

It was around midnight when we went to this port, walked down this rickety wooden pier, and then jumped on this fishing boat. We were wandering around for like 30 minutes, weaving through all these gigantic vessels, and me and Theron had no idea what we would get on. It’s funny, because we were approaching this kind of moderately sized fishing vessel and thought, “Well, it’ll be amazing no matter what happens.” But we both wanted to get on a big ship, [laughs] obviously. And eventually we weaved around that fishing vessel and saw this big thing, just sitting out there by itself. It was obvious that was the ship we were on.

When we got to the ship there were pretty big swells and we were curious how we were going to get up there. The crew just, of course, roll a rope ladder down and Theron says, “Oh, I didn’t tell you, I’m totally scared of heights.”

They were also just screaming at us from above, because the ship was seven stories high, it was windy and just so intense. Anyway, we climbed up the vessel, and it’s this crew from all over India. We found out right then that they exclusively work on these ships that are on their last journey to be demolished. People actually do create sabotage with their ships because they’ve been on them for so long and there’s this attachment and this love for the ship. Sometimes in the middle of the night somebody disconnects something that they know is going to be a big problem. So that happened so many times that [new crews are hired and sent out]. That’s these guys, and there’s probably like two hundred of them out there, and they’re just all over the world getting on ships.

Once aboard, how did you approach shooting on the ship with limited time and a finite supply of film stock?

The trip took six or seven days to get to Bangladesh. The first two days I could not film because I just didn’t know what to do. With celluloid, you don’t have an endless stock. I just thought I’m gonna blow it if I use it right now, because I’m just not feeling it when I look through the camera. I was actually a bit concerned that I wouldn’t film anything.

While leaving Singapore, right when the Strait of Malacca opens up into the Andaman sea, me and Theron went up to the front of the ship because we were kind of curious, because that was one of the most heavily pirated areas at the time. Then the crew turned off all the lights. They don’t want people to know that they’re driving on through.

We’re looking down and the ship’s riding pretty high because there’s no cargo. It’s plowing through the water, and all of a sudden the water becomes brighter and brighter. Then it becomes really bright green and sparkly. It was plankton generating this electricity. I’m like, “Oh my God, we have to go back and get the camera!” Then Theron said, “It might just go away in a second. Maybe we should just watch it and just take it in.” Then a slithery thing comes from underneath the triangle of light in front of the nose of the ship. We’re looking seven floors down and can tell it has girth from that point. It must have been large and at least 15 feet long. It almost seemed like it was some sort of weird illusion.

We watch it for a while. We don’t say anything. We can’t even talk. Then another one comes next to it. It’s a little smaller and it’s moving differently. So we know it’s not an optical illusion at that point. Then more and more come and there’s nine or ten of them just in that light.

“Are they driving us somewhere, these sea serpents?”

Eventually we see one slowly zoom off and disappear, and then another one disappears. Slowly as that’s happening, the light decreases. It’s like a fade out, pretty much.

I read later that there was actually this glowing green line that you can actually see from space during certain times of the year at the Strait of Malacca. In the Thirties, there was some sort of recording where there were like five hundred of these things, which I think are oarfish. Very deep water creatures. Large ships actually can get their attention from the friction of the movement below.

The next day, I woke up refreshed. I really just wanted to capture everything at once, get these objects and the people at the same time. I was interested in this emotional take where I’m filming not knowing what’s around the corner. I wanted this spontaneity to happen for me as I’m shooting this ship, because I never–I had been on a ferry ride from Vancouver to whatever island in Canada. That was the only time I had been on a big boat, and it wasn’t that big. Being in this space, it was almost like it was evaluating my fear of it. It was the excitement of this emotion that I really wanted to be displayed.

I was excited to use light in a very minimal way, just opening up the lens, opening up the

aperture as little as possible, and seeing what exciting errors could take place. This mystery within shooting the film was a huge aspect of the adventure. There was some stuff that was impossible to get anything out of. It was too dark, stuff like that. But it was worth the risk.

We used a Super 8 camera at one time. Theron called it like the plank cam. We attached it to this piece of wood. One person controls the left side from a rope that we dropped down along the edge of the bow and then one person controls the right from [the] front. We just strapped duct tape to this camera and let it run. We dropped it against the side as the ship was zooming along. There’s a shot where you see the nose of the ship from close up and you see the water sparking, flying out, and then it takes you in front a little bit and then you go back. It’s the wind that’s gliding it, but it’s pretty smooth.

One topic we did not have time for discussion at Spectacle was the use of the 16mm Chinese propaganda films and other materials you find. Can you elaborate on the experience of uncovering these artifacts and being able to incorporate them into the film?

JB: When Theron and I opened that door, we realized that there was a mangled film projector in there, and then a closet full of metal cases of 16mm films. It was crazy amazing. “What do we do with this?” We started taking a bunch of cases out and looking at them, just spooling off the film and seeing what the images were. Being an archivist, we carefully put everything back.

I had a meeting, either like that day or the next day, with the captain to ask how we get this film off this ship. He said there was a problem with the weight of being able to take that material off the ship because we were going to get to the beach by the lifeboats. There’s an exact weight measurement that you could use in a lifeboat and he said we would have to have some people swim ashore if we took all the cases. That would be ridiculous in every sense. But at the time, I was like, “Oh my God, all this film! What do we do?”

He said I could fill up my duffel bag, so I dumped a lot of my clothes there and put what I could in the bag. We pulled down a couple cases and we made up our own reel. We pulled those shots from maybe seven or eight different films that made it into the compilation in Scrap Vessel. It was a very manual process. Sitting on the ping pong table with this bright light, reeling through them, and ripping them [out] with our hands. I spliced them when I got back to CalArts.

While you didn’t get to capture the sea serpents you saw, we still get other types of serpents in the film’s conclusion in the form of molten rebar. The re-rolling mills are presented as Chittachong, but you actually filmed in Gujarat. Can you explain where that fell during the shooting process?

I had filmed the re-rolling mill during the week before boarding the vessel. I obtained access through a college student I had met after presenting my film project at Bhavnagar University in town. A bunch of kids came up to me after class to talk to this “foreigner.” One of the kids was like, “Oh, my father actually works in a re-rolling mill.”

“What?”

“These mills that reprocess the steel and make rebar.”

“Oh, that’s really interesting.”

“We can go over there today if you want.”

So we went. Most of the people who ran these rebar facilities lived on the premises and were among the Jain Dharma religion. Always wearing full white, extremely vegan, very interesting. I talked to this student’s father. In this industrial area, he told me they do what they call load shedding—which is something that is going on in South Africa today, for example. The electricity is not great in these places, so what happened is that they would run the power at night. Maybe like 8pm to eight in the morning is when these facilities are open. I went there to check it out and filmed something that night. Around that time, I got this call that if somehow I commit to Singapore within a few days and get my friend there, we can board this ship.

A day or two after the ship beached, we flew to Bombay, got back to Gujarat on a 12-hour train ride, and filmed there for three straight nights. There’s barely any other lights but that golden, yellowish burn of the heated metal. Everything else you could see was kind of illuminated by this stuff. I was, of course, thinking about that as I was filming.

The rebar process itself, there’s nine times where they’re reducing the size of these bars through these two metal rollers. They have a little gap in between. Before, it’s almost the size of a fence post. It’s pretty large. You plow it through and somebody’s at the other end with tongs and then they put it through another one, and then it gets stretched and stretched out until it’s normal rebar size. In one of the last shots, once it gets to the spaghetti zone –just really thin—I remember almost losing my foot because of the bar shooting out further than it did the first few times.

It was a super volatile space. I did hear stories of some bar hitting someone’s shoe and wrapping itself around—this really awful death scenario that probably happened more than once.

There’s one break or two during the shift where everybody stops what they’re doing for a chai break. I remember gathering with everybody. They had these little metal cups full of chai. One person handed me the cup and I just dropped it because it was scalding. Nobody laughed, but everyone was sorry. Then they wrapped a part of a towel and wrapped it around the cup. It was one of those signs where you realize how tough these people are. What an insane job to do.

There is a synergy between the film material itself and what you’re capturing that comes out in its texture. The film surface has visible scratches and holes, and takes on the quality of being an old, dusty body just like the ship. Was this look achieved consciously or was it something that occurred organically because of the environments you were filming in?

A bit of both.

On my way back to India [to film at the re-rolling mill], I had an issue with my film possibly being flashed. [Airport security] had to x-ray my film.

I was worried about having my film flashed again, so I went to AdLabs in Mumbai. That’s the place where they pretty much developed, at the time, every Bollywood film. I wanted to have one print just to see what it looked like. And the one print I had made is very visible in Scrap Vessel. It’s the one where there’s a huge scratch down the right side.

“Oh my god, I wasn’t cleaning my camera enough. Does all of my film have this one big line?” I almost had a heart attack, but I managed to be able to get a loop and check some other film and it didn’t look like they had that scratch.

[The footage] was kind of mix and match. Some of the film looked really good. It could have been the baths [they were developed in] or how they were stored on the ship. Anyway, there’s a whole variety of different looks in the film. When I went back to school, I saw the footage and I was horrified.

Probably a year went by, and then all of a sudden, I loved that footage. The line and the graininess and how the print looked. I just thought it was kind of amazing. It was a weird turning point. That made me look at the rest of the footage and then try to do things with it. Mostly re-filming footage on the optical printer that we had. Basically getting print film and putting it through a projector and then having it be re-filmed. It builds up contrast and it creates this really wild look. I started doing that with the really clean footage, [trying to even out the film.] That’s what I did while I was at school.

When I was actually editing the film, I couldn’t see at all what I was trying to do. I didn’t feel anything. I made a 10 minute film to graduate with. It was garbage.

Everybody was like, “Your film is so great. It’s perfect. I’m telling the truth.” Then finally I talked to Thom Anderson [while he was smoking a cigarette outside] and he just destroyed me—in a good way. “I don’t know how you do it, Jason, but it’s like Chris Marker but with no dialogue and somehow didactic at the same time.” [Laughs]

I realized I needed time with it, where my memory would fade a bit, where things would just be a little less clear visually and what the order of the trip was in the first place.

I’ve also been interested in your use of intertitles and how you pieced the film together with them. They help create the effect of a recollection or a diary, but the way they are written is pretty sparse as well.

Deciding on how to edit [the film]…

“Should I throw everything in? Should I be very selective? How best to keep this mystery but not overdo things?”

I did feel like it would be a little more distant, having text. I wanted it to be embedded in the film. The font that was used for intertitles is very steely. It’s almost like a branding on a box or machine-like. It felt personal with what I wrote though. I have a hard time hearing myself speak too. There are one or two shots where my voice is there in the film, but I felt like you’re really with the text itself. I wanted it to be like archival material just like this 16mm film stock. I wanted everything to be flattened into that world.

The biggest thing to learn about the actual editing for me was to create this film in a way where it would be a memory for me, and that’s saying that the film is not 100% true. I only had one pirate incident in the film, but two incidents actually happened. I had combined elements of both to create that one story. The first pirate incident, somebody was trying to cut off pieces of the brass propeller. During the second, two pirates actually boarded the ship and their goal was to steal the mooring rope that they use to tie the ship to the dock, but they were cornered by crew members and decided to leap overboard. When the pirates were in the water, the crew began throwing the pots, pans and dishes at the pirates that they took from the mess hall. Combining these two moments made sense.

I wanted to do something that kind of simulated a dream, but also reality. I guess you could say that was ego-driven as well. I just had no idea how people would respond to this, because it was such a personal memory that I was really trying to uphold. Some people I know didn’t like the edit at the end, because they felt like there are all these other things that I should have developed. I never felt that way. I felt like that might be another film down the line or something.

For me, it was a fascinating idea to kind of recap this basically like a scrapbook. Having something that felt tangible in my brain that never even happened, but at the same time where there’s enough blurriness throughout that I wonder, “Did that really happen?” Keeping that mystery in my head makes me appreciate the film.

Stephen Jeffrey Cappel projects movies and lives in New York City. He programs and writes when he feels like it.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider tipping the author and/or supporting Ultra Dogme on Patreon, so that we may continue publishing writing about film + music with love + care.