by Tyler Thier

AI can “predict” the future, by which I mean orchestrate possible futures. We’re far enough into the technology’s evolution that machine learning and predictive text are functions of the past; it now possesses the ability to simulate ethnically cleansed utopias.

Donatella Della Ratta, in reference to a viral AI-generated video of an “idealized” and “post-occupied” Palestine shared by Donald Trump, writes in a recent article for Verso that,

[The language surrounding it] only rhetorically conceals what’s underway: the logistical staging of ethnic cleansing and mass displacement of the Palestinian people. Truth is, the AI video has never operated as critique, cautionary tale, or even simply “just satire” – which its makers have indicated as its original purpose, before the US President decided to spread it on a global scale. Rather, it functioned as a prophecy. Generative AI acted as a quintessential visual infrastructure, a prophetic apparatus making visible what had previously been politically unspeakable and unthinkable. By rendering such visions into photorealistic form, AI granted them legitimate entry into the global public imagination. What once could hardly be whispered was rendered visually plausible, and in aesthetically pleasing form.

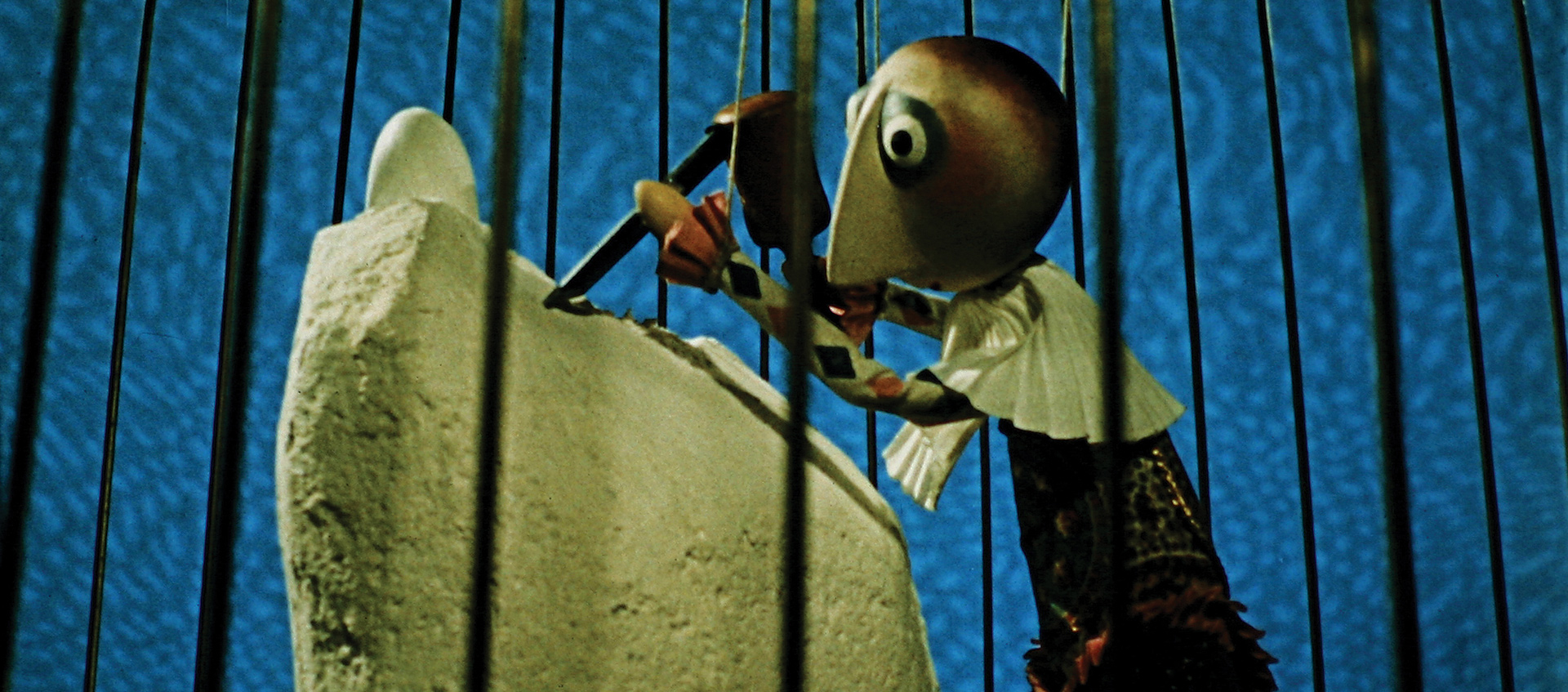

In a lot of my writing, I tend to get obsessed—almost conspiratorially paranoid—over contemporary visual culture and how it mediates our reactions, our politics, and our perception of reality itself. What Della Ratta describes is at once the most vicious example of this in action, and only scratching the surface of what’s to come. So when I saw Jiří Trnka’s The Hand (1965) not too long ago as part of a summer series at The Met, I was ecstatic over its handcrafted artistry, the tactile mise-en-scène, chaotic humor, and thoughtful, often abrasive, use of film technology. It seemed like a retroactive antidote to everything I had been feeling over technology in the present. The filmmaker’s final (and most honored) work is a kaleidoscopic commentary on fascistic control—a giant hand tries to break into a sculptor’s home and force him to make a monument to itself. By the end, the artist is not only literally puppeteered by the god-hand, but ultimately silenced for good. A razor-sharp finale to Trnka’s career, as he, too, was for a time an instrument of a totalitarian regime.

The Hand masterfully balances childlike playfulness, boasting wild shot compositions and camera movements within an otherwise static, dollhouse-like set, and vibrant objects that get built and smashed and rearranged all over again throughout the struggle; and resistance in that the artist does defy the hand for a good while, until it grows more relentless; and flat-out pessimism, complete with the sculptor’s bondage by puppet strings (himself being a puppet in the first place) and eventual death, leaving a monument to a handsy tyrant standing in his wake. Fascism wins.

The technology available to Trnka by the end of his career was becoming more intuitive. He was, in The Hand, able to employ an excitingly whiplash collage of visual and editing techniques that zoom and pan and pivot our perspective from large to small details within this very bespoke environment. The result is a cartoonish dystopia that feels all the more viscerally real because it contains depths through which the camera dips us in and out. An ideological lens materializes from these effects, producing laughter and terror all at once, and it’s not quite clear by the end whether we’ve been viewing this artist’s plight from the hand’s perspective. When I exited The Met screening, I was determined to trace this lens back through his body of work. In our time, where genocidal campaigns can easily be perpetuated, smoothed over, or blueprinted for success with the help of advanced technology, returning to an aesthetics that did the opposite lends one just a smidge of hope.

It turns out that Trnka, once considered the Walt Disney of Eastern Europe, was a committed antifascist in nearly all of his artistic work. No matter how assertive or reined in his imprint turned out to be on any given project, it always seemed locked into a death drive towards crafting defiant dreamscapes. Ironically, his other moniker as designated by critic Stephen Bosutow, was “the first rebel against Disney’s omnipotence.” Trnka’s style, which fused puppetry with 2D figures, animation with live-action, stop-motion with still photography, and a variety of other multimedia collage techniques, registers as fresh and frenetic and radical even today. This versatility enabled the animator to interrogate heavier themes—he often instilled his work with a sense of metacritique that consistently involved the entanglement of technology and power, art and populism—whether productive or downright malicious.

An earlier, more “rudimentary” entry in his filmography might seem like any other Disney cartoon that Trnka actively pushed back against, but already it shows glimmers of the artist’s penchant for multimedia and agitprop. Springman and the SS (1946) immediately announces itself as a satire of Nazi occupation; a caricature of a Gestapo officer donning a Hitler stache works with his hive-mind of identical Aryan SS goons to sniff out Jews through apartment complexes and in the streets. They detain some pet birds and rabbits, a dog that was pissing on a Nazi statue, as well as a mechanic’s advertisement (a silhouetted cutout of a strong, labor-proud man) that just so happens to depict a sickle alongside other tools. Might as well have cued the Soviet anthem at this point, because Mr. Gestapo also sees a man dancing and briefly perceives him as a stereotypical Cossack. Another arrest for the books.

Eventually the film becomes a cat-and-mouse slapstick where a chimney sweep doubling as a vigilante uses his spring-activated tools to terrorize and outwit the SS troops. Notably, especially during its latter half, Springman makes use of hyperreal flourishes—like smoke that appears to be live-action overlaid onto the 2D visuals, a billboard with a photorealistic ad that comes to life through what looks like rotoscoping, backdrops of high-rises that are actual photographs, and subversive moments including two gay SS officers caressing each other on a bench, and the Nazis halting their pursuit to do a quick heil whenever they’re in the presence of Third Reich memorabilia. Deliciously acidic, and even more so when you consider the film’s Disney-presenting animation style. This sense of mixed media and tactility becomes difficult to ignore through Trnka’s later work, especially when he moves fully into puppet/stop-motion territory. It’s as if surrendering to just one “form” or “genre” would be akin to complacency.

The Gift (1947) took these innovations and ideas even further. It’s a mix between live-action and 2D animation, bookended by a flesh-and-blood narrator who’s working on a script. Continually, the animated run-through gets intercut with the narrator’s self-revision, offering edits that manifest themselves on-screen as sensationalist interjections, forcibly heightening the drama and erasing any “rough edges” plot-wise.

Among the changes that activate mid-story are a rich man who has only one servant instead of many, since “We must not show that a single person has so many servants”. Backdrops, seen through a window and depicting different landscapes, are rotated out like title cards, the Leaning Tower of Pisa needing to be “straightened out” so it doesn’t look like too much of an aesthetic blemish, and swapping the antagonist (a secret lover of the rich man’s wife) from a white gentleman-type to “a savage, and the action should take place in Honolulu.” Also, god forbid the rich man gets humiliated as the writer intended; no, he prompts himself to change it to the affluent protagonist triumphing, a happy ending sealing the deal on this supposedly improved script. Classic satire of art and enterprise at odds, but Trnka bolsters it with ferocious critique through hands-on, Brechtian interventions.

Trnka’s later work turned primarily towards puppet cinema, but never slighted on the multimedia agitprop. In fact, they only grew more agitational and dark-tempered as the years passed. The Devil’s Mill (1949) is a strange one; we follow a nomadic, not-particularly-talented musician/war veteran who stumbles upon an old mill that’s been invaded by a demon. It’s part haunted house narrative and part anti-feudal parable, where the veteran engages in a melodic standoff with the deity and wins the mill back for its dejected owner. The shadow work, the stop-motion, and the use of sound here work seamlessly in transporting us to a folkloric land where haphazard evil lurks in the darkness. Occupation, both physically and psychically, emerges as the true villain, with Trnka growing only bolder in interrogating it as we progress towards The Hand.

The Passion (1962) and The Cybernetic Grandma (1962) bring Trnka’s artistry fully into the contemporary. The former is a breakneck sidescroll of a short, where from birth a boy is so obsessed with mechanized speed that it becomes all-consuming well into adulthood. Humorously, he drives through various collage/dollhouse-like tableaux (familiar, no?) stealing trinkets and tools to help rev his engine even faster, and faster, until he finally comes crashing headfirst into a funeral procession. His one-track mindset literally sends him to his grave. It’s full of pop-art visuals and lively cinematic framing despite capturing someone’s conveyor-belt journey towards death.

The Cybernetic Grandma is a more brooding work; we follow a child and his grandmother traversing the ruins of a space-age world. Somewhere along the way, the grandma disappears, and a robotic counterpart (not at all a lookalike) attempts to take her place. The result is a cold, harsh alternative to the protagonist’s actual grandparent: a representational corruption. The film’s visual style is restless despite its glacially contemplative pace. Alphabetic computer monitors dance with spellings, animated blobs consume the screen, complicated machinery whirrs and lashes about with no discernible function, model airplanes and dilapidated space shuttle hangars recede into the deep, opaque shadows of the camera’s periphery. It’s maybe the most textbook “dystopia” of Trnka’s career, but still distinctly his own.

One could get lost in the details of Trnka’s collages for days. They are weird, funny to the point that it feels wrong to laugh, sometimes completely mind-melting and near-psychedelic. But in every single film, he conveys a sense of hybridity that defies a singular mode of representation. Trnka’s work is impossible to classify as solely stop-motion or animated, as absurdist or realist, as live-action or puppetry; he exists in this interstitial zone that some may label “visual artist who makes films.”

But really, the zone he occupies is one of anti-occupation object cinema. Ceaselessly, he mashes concrete elements (puppets, archival photographs, hand-drawn animations, real-world tools, actual humans) together to create a visual infrastructure that resists isolation and will for that reason always be protected from the taxidermy of generative AI. As Della Ratta notes,

Generative AI does not mirror the real, but extracts patterns and latent affinities from data, recomposing them into plausible visualization of the future. Like the photographic gaze, AI does not just show what is, but hints at what could (or should) be by activating the imagination’s latent potential to recognize and accept suggested combinations as meaningful.

Trnka never had the existence of AI to engage with during his career, but he constantly toyed with the dangers of fascism and the loss of autonomy it fosters, often through technological means and within dystopian visions that could always be identified as such. His hyper-collagic aesthetic enshrines a sense of critical distance and an avoidance of perfection or smooth edges or “aesthetically pleasing form.” In other words, the radical inverse of AI renderings.

Is Trnka the only filmmaker to revisit if we wish to process AI’s present onslaught via the past? Certainly not. But he is a hell of a great example of artistic technology employed for the purpose of combating complacency and investigating the consequences of totalitarian futures. If visual output in the current moment includes corporatized curation of a post-eradicated culture, what more can we learn from Trnka’s antifascist visual ecosystem? Furthermore, was this essay just a Trojan horse intended to spread Free Palestine solidarity? Absolutely. People are dying, world leaders are posting racist AI utopias, Trnka is rolling in his grave, and Springman is nowhere to be found.

Tyler Thier is a cultural critic based in Queens, NY. His previous writing can be found in Senses of Cinema, Little White Lies, JSTOR Daily, In Review Online, The Brooklyn Rail, and more.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider tipping the author on PayPal and/or supporting Ultra Dogme on Patreon so that we may continue publishing writing about film + music with love + care.