by Faranak Nateghi

At Il Cinema Ritrovato 2025, as part of the Cinemalibero section dedicated to marginalized and suppressed voices, Journey (Safar, 1972) by Bahram Beyzaei from Iran was screened, its timing coinciding with Israel’s recent attack on Iran. This synchronicity underscored the timeless and transhistorical dimensions of Beyzaei’s work, which itself was created during a period when Iranian society was enduring a different form of fear and insecurity, the last decade of a political order.

Journey was produced by Kanun (the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults) in response to the need for domestic productions in its newly established film festival. At a time when the country was on the brink of revolution, the collapsing regime sought to create agencies of aristocracy and extravagance as a diplomatic façade. The Kanun Film Festival emerged as one of these initiatives. Although presented as a prestigious international event, hosted directly by the empress in praise of the royal family, the festival suffered from minimal Iranian contributions. Becoming an embarrassment for its organizers, the lack of Iranian contributions prompted Kanun to commission and allocate artists to produce films specifically for the festival. Out of this contradiction emerged another contradiction, an opportunity for prominent Iranian filmmakers who would go on to shape the foundations of the Iranian New Wave, supported within a context that the films themselves criticized.

Journey follows two children, one endlessly searching for his lost parents and the other seeking a way out from his harsh, exploitative employer. Alienated in their own hometown and suffering from hunger, both are threatened by a hostile environment in a city that is rapidly developing, but has no place for them. Seen in the context of the festival, the film reveals the ontological depth of Beyzaei’s allegory: his opposition to power structures transcends the cinematic frame, pointing to the reality outside it, as the children’s bewilderment unfolds within the very city that simultaneously claims to celebrate the cultivation of artistic sensibility in the younger generation.

Analyzing Kanun’s festival also reflects a broader issue of the period: the royal family’s attempt to impose an unusual form of modernization on Iran. Lacking the infrastructure and foundational transformations necessary to sustain it, this effort resulted merely in a replication of the surface characteristics of modernity, a crooked way of modernization that can be extended to Iran today, as any attempt to acquire power is ultimately condemned to collapse. The contradictory city at the heart of this narrative is Tehran. In Journey, Beyzaei reflects on this matter through constructing a dystopian vision of development, where the inhabitants themselves become spectacles of this fragile civilization: an old man carried on a board, a sick figure trying to pull the protagonists down like a swamp, and the children beaten for stealing a loaf of bread.

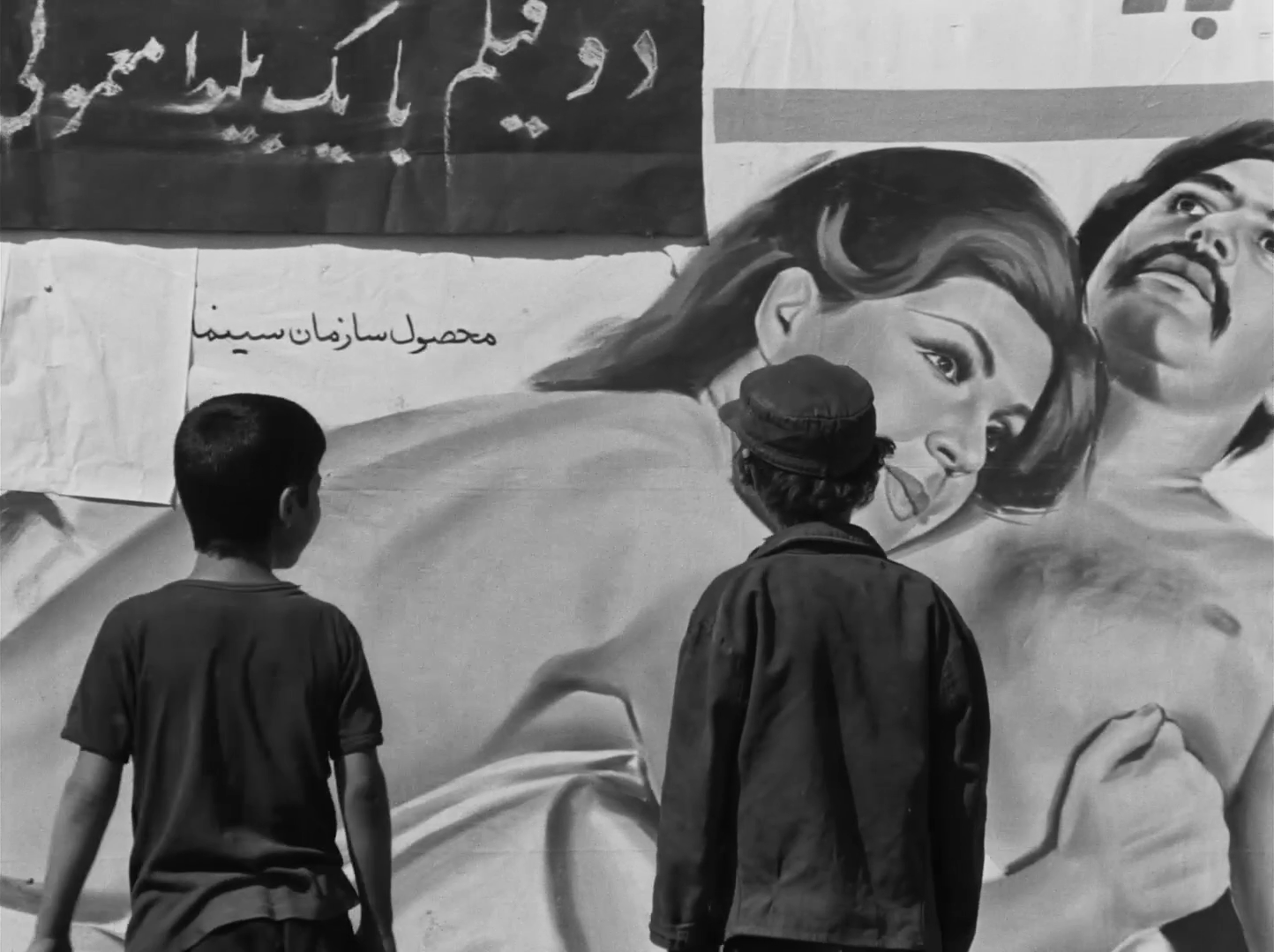

The city owns wheels, ladders, doors, posters, food, a camera, and parents, yet none of them belong to the protagonists. All these props and spaces appear in their metaphorical dimensions, as is characteristic of Beyzaei’s cinematic language. A movie poster featuring the image of a seductive woman, an emblem of mainstream attraction and entertainment, stands in the background of the threatening gaze of a stranger, suggesting a kind of development that excludes and intimidates. This is followed by a woman fully covered in a black veil, lighting candles as a religious act, only for the children to steal them. The protagonist’s desperate cry to God, “make my wish come true, not hers,” reveals the futility of both spectacle and ritual in answering their needs. The imposed modernity finally appears as a mirage, echoed in the dialogue of the mad figures hanging on ladders, laughing and saying: “You came the wrong way.”

This confusion is bound to a hope they are desperately holding. If there is any possibility of dreaming up a better future in this age of hopelessness, it can only appear as imagination or as a false sign. No matter how fake, society remains open, eager, and ready to be hypnotized by it. Take, for example, the scene where the protagonists, planning to pickpocket for food, distract the crowd simply by staring into the abyss. In an instant, the people gather, deceived, yet compelled to follow this nothingness(Fig. 1 and 2).

The feverish quest for parents—those who own addresses, locations, and fixed spaces—seems so implausible that it becomes an illusion. Searching for guardians here is not a sentimental act to soothe the melancholic needs of being, but rather a material quest for identity and recognition. Having an address is the answer to all needs: not only the material survival of the unemployed friend but also the existential inclusion within this expanding city. The protagonist is so captivated by this illusion that even after the imagined parents reject him, proving he is not their lost child, he insists on being accepted as one. Now he stands beyond the door, in the realm of the outsider, so close to being modernized and included, and yet he fails. Still, he remains determined to find another address and another potential set of parents the following day. During their pilgrim-like walk toward this destination, he plans his home, his power, and the possibilities he will offer his friend, even promising things he does not own. Embodying the hope for salvation, he invites his companion to sacrifice his options to achieve the impossible, the inaccessible.

While symbolism in Iranian cinema is often limited to coded narration to elude suppression—sometimes leading to self-censorship, where symbols become fixed icons, reducing imagination to a mere retelling of presence—Beyzaei employs it differently. Rooted in his theatrical tradition of storytelling and performativity, he integrates symbolism into mise-en-scène, narration, and performance. This staging begins with the cinematic frame itself, from the fluidity of the camera’s movement to the articulation of dialogue. When characters stop to speak, laugh, fear, or cry, each gesture refers to its counterpart in the real world. Beyzaei acknowledges the fabrication of this system of meaning as something constantly recurring in an atmosphere charged with enactment and movement. This is where we can revisit our confrontation with a mise-en-scène filled with wheels, doors, ladders, carriages, and cars, where even a dying man, lost among ruins, seeks life within the debris of modernization.

Extending this reading to Iran’s present moment, these themes continue to resonate. Fifty years later, the film is screened in Bologna, Italy, not in its hometown, restored from found negatives abroad, while the destiny of its original reels in Iran remains unknown. It is now being watched in a cinephile celebration, while Tehran, the very un-modernized city of Journey, is again under bombardment. The city may have transformed, yet the two children remain familiar, still lost in the cityscape, rebelling one day, fighting the next, constantly menaced by both insiders and outsiders. The same contradictions persist in a society waiting for a savior to pass through life, drifting among wheels and ladders, doors and carriages, sickly figures and overwhelmingly ideological posters.

Faranak Nateghi is a film researcher pursuing an MA in Film Heritage within the FILMEU network. Her work examines the intersections of Iranian film history, ideology, and archival theory, exploring how film archives mediate collective memory and historical absence.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider tipping the author on PayPal and/or supporting Ultra Dogme on Patreon so that we may continue publishing writing about film + music with love + care.

Ah, *Journey*! Still staring into the abyss of modernitys mirage, arent we? Beyzaei masterfully constructs a Tehran where even the props seem to mock our quest for belonging, much like finding an address that isnt on any map. The protagonists desperate, delusional search for parents who dont exist is tragically hilarious – a perfect example of Iranian cinemas unique ability to blend pathos with the utterly absurd. While we debate the ontological depth, all I can say is, maybe the real modernization failure is that cities keep building ladders yet forget to provide rungs. And isnt it quaint that even a dying man in the ruins clings to life, proving were still utterly hypnotized by that false sign, no matter how fake.