by Patrick Preziosi, edited by Forrest Cardamenis

From the early 1990s onwards, film and television were trying their best to keep pace with the emergence of the world wide web, its growing popularity beginning to be attached at the hip with its democratization. Thus, there was a bombardment of everything from mere passing references to narrative frameworks and even marketing tools that drew their inspiration from this development. With David Blair broadcasting his cult object Wax: Or the Discovery of Television Among the Bees across a handful of computer screens in 1992, the release of 1995’s The Net, the use of online dating jokes and horror fodder on both network sitcoms as well as The X-Files, and the previously unprecedented marketing campaign of 1999’s The Blair Witch Project, there are innumerable instances of the burgeoning service even just nominally worming its way into popular culture. Across all mentioned, there’s a through line of eagerness to co-opt the internet and parcel it into digestible iterations. The variety of depiction gestures towards the opaqueness at the web’s center: the absence of any sort of functioning guarantee, of safety, of correct use, or anything in between.

For an acknowledgement of the sheer unknowability of such an entity (and how that informs its basest function as a connective platform), a Stephen Posey directed episode from Buffy: The Vampire Slayer’s undervalued first season––the cheekily titled “I Robot, You Jane”––is the most disarming in its prophetism. The ‘90’s artifacts of the show––specifically characters’ relative unfamiliarity with the internet––only bolster the unnerving effect of the standalone villain, a medieval demon named Moloch, who, after being trapped in a book of scripture for centuries, is let loose on an embryonic version of the web after Buffy scans the imprisoning pages. Moloch will later assume a quasi-corporeal form, but his virtual self is what retains the most frightening power, with a computer-bound Pandora’s Box of mind-control and ensuing violence opened within an unfamiliar technological realm as soon as Buffy presses “scan.” He first exists as a pop-up scrawl of digital text on the desktops in the school’s computer lab, where he ensnares students Fritz and Dave under his spell upon their viewing, instructing the two to kill Buffy. There’s a presumed element of mind-control in how Moloch’s computer missives draw in his lackeys, but Posey also draws attention to computers and their authoritative breakthrough; as a beacon of a not too far off future, it’s entirely reasonable these two highschoolers would think to so easily obey a message sent to them personally from the digital ether.

Posey’s episode isn’t interested in fashioning itself as an anti-cyberspace, afterschool special screed. Instead, it captures a brief moment on the precipice of the internet’s omnipresence, with just a dash of hopefulness personified by the school’s computer-lab teacher, Ms. Calendar, a self-professed “technopagan” who’s as instrumental to Buffy’s defeat of Moloch as the teenager’s own mentor, the comparatively old-hat librarian, Giles, who admits to finding computers intimidating (he and Ms. Calendar flirtatiously debate the technology’s necessity).

The surprisingly multivalent narrative strands of “I Robot, You Jane” (one of which, unsurprisingly, concerns online dating) is in part achieved by its relatively mundane setting, which centers on one Sunnydale High School. The teenage-soap underpinnings are a far cry from the merciless dystopias of Johnny Mnemonic or Strange Days––both released only two years prior––and thus stand as a worthwhile portrayal of a world being forced to accept both the virtues and the vices of the web, the high school drama-plagued teenagers acting as personable audience surrogates. In an initially much less mythological interval, Buffy’s companion Willow––who handily fulfills the social outcast archetype––thinks she has found love through an online dating service with a boy named Malcolm, a plot point that tentatively brings forth the prevalence of social media to come less than a decade later. Posey veers from this nuanced development into another battle of good vs. evil, considering the user Malcolm is a disguise for Moloch, but the dichotomy is established nonetheless.

Even if Buffy has managed to momentarily stave off Moloch, a vengeful demon still portends a larger evil bubbling to the surface, and if he’s unleashed via just a common schooltime activity, what else could be on the horizon? Although the two projects couldn’t be further apart, the threatened, all-encompassing reign of Moloch finds a spiritual companion in Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse, which, released in 2001, bridges the turn-of-the-century cyberspace gap with “I Robot, You Jane.” Pulse was then the latest entry in a (still) incredible run of films by Kurosawa, that, beginning with the success of 1997’s Cure, gave the director the rightful reputation of a supreme formalist, one who could suddenly rearrange the drab building-blocks of our everyday into an atmosphere of discomfiture. The icy precision of the scares are abetted by little more than a pan of the camera or a change in the weather.

Kurosawa, similarly to Buffy, relies on a stilted element of teen romance, that even though not directly wedded seamlessly to Pulse’s horror, provides the necessary real-world analogue to intensify the innate risk of the internet. The web may have ushered in a depopulating Armageddon by the close, but Pulse’s terror is stoked by two teenage girls who try to find their missing computer-programmer friend. Not dissimilar to one of “I Robot, You Jane”’s most unsettling images, which depicts the dangling feet of a hanging in the computer lab (as overseen by Moloch), this friend––once found––presumably commits suicide. However, he more willfully disappears, as if commanded to do so by some unseen external force, fading into a splotchy black stain on the wall. From there, a small smattering of intersecting characters––the two friends, an internet novice, and a post-grad computer scientist––try to survive the onslaught of computers acting on their own accord: starting up, playing videos, offering unnerving, Moloch-reminiscent typed-out propositions, such as, “would you like to see a ghost?” Kurosawa portrays his characters as susceptible to the sovereignty of this technology, just as quick as David and Fritz are to open mysterious links and videos without second guessing. Even in 2001, Kurosawa was able to capture that awful moment when you realize you’ve opened something you instantly regret, especially near the beginning when a young man is suddenly, unwillingly viewing videos of ghosts in spookily bombed-out rooms.

Pulse is a film of gaps, its narrative logic gradually dissipating as computer-born phantoms begin to proliferate across Tokyo and outnumber the surviving flesh and blood humans. There’s no stemming the tide, as Kurosawa succinctly asserts from the beginning: a character proficient in navigating the necessary technology is also the first to succumb on-screen to the spectral disintegration that becomes the film’s preferred method of death-dealing. Where your garden-variety dystopia presents a world in which insidious technology is an accepted norm, Kurosawa instead includes nearly every character’s initial encounters with the internet. Experience––or lack thereof––with computers is entirely null in the face of this encroaching apocalypse. Because Pulse is set within a contemporary cityscape, the wide-reaching harm of this ghost in the machine is pronounced via simple gestures within Kurosawa’s mise-en-scene, such as a convenience store or library entirely void of staff and patrons, or a commuter train which just stalls in the middle of nowhere, its only two passengers marooned. These moments can become all the more fatal depending on circumstance, such as a plane crash near the close, which obviously occurs in the sudden absence of a pilot.

There’s no rationalizing the way Pulse spirals from spooky, low-res videos opening on random computers, to terrifyingly statuesque, black-clad ghosts, and then to mass suicide/evaporation. Absence of reason is the film’s unifying feature, and also what makes it so frightening. There’s a senselessness present, but it’s mostly conveyed through the anxious comportment of the characters and their inability to quantify what’s happening around them, not with mere gore or bloodshed. Repeated contact is made with the ghosts, who appear to obey no expected horror movie logic, inflicting the characters with a lasting dread rather than harm. Like Posey’s approximation of the internet in Buffy, Pulse isn’t an exclusive document of doom-saying, but a sober mapping of the effects of the web and its dangerous potential as both an autonomous entity and one that can easily be wielded by an ostensible villain.

As posited by Posey and Kurosawa, espousing any sort of “right” way to use the internet is pure folly; their respective projects invite accusations of a certain, technophobic nihilism, but their incorporation of the web is admirably straightforward, fully cognizant of its inevitable permeation into every aspect of humankind. Still, “I Robot, You Jane” and Pulse are encased in a kind of early-internet amber. Each project respectively marks a watershed moment on the internet timeline, one where computers were becoming more accessible in institutions such as schools (Buffy), and then subsequently became an even more common accessory of the home and other personal spaces (Pulse). Moreover, both “I Robot, You Jane” and Pulse frame this unfamiliarity as symptomatic of the ghosts themselves. In the former, before his reign is enacted, Moloch asks, via his computer-text form, “where am I?” And as has been customary with Kurosawa, his ghosts fitfully impart a tragic waywardness; the phantoms of Pulse appear almost randomly, suggesting a purgatorial wandering on their part, as if they themselves are just as bereft of control as the protagonists.

The 2010s equivalent of Posey’s ghost in the machine and Kurosawa’s malleable visual palette is the Unfriended franchise, “desktop-horror” films that unleash all kinds of internet-bred horrors on varied youths. The first film, 2014’s Unfriended (directed by Leo Gabriadze), introduced a new kind of hyperactive cinema, with constant flitting between tabs, applications and conversations serving as the film’s ostensible “action.” A Skype call between a group of high school friends is soon invaded by a mysterious user named billie227, who the students soon learn is the beyond-the-grave incarnation of Laura Barnes, a classmate who each member of the party bullied into suicide.

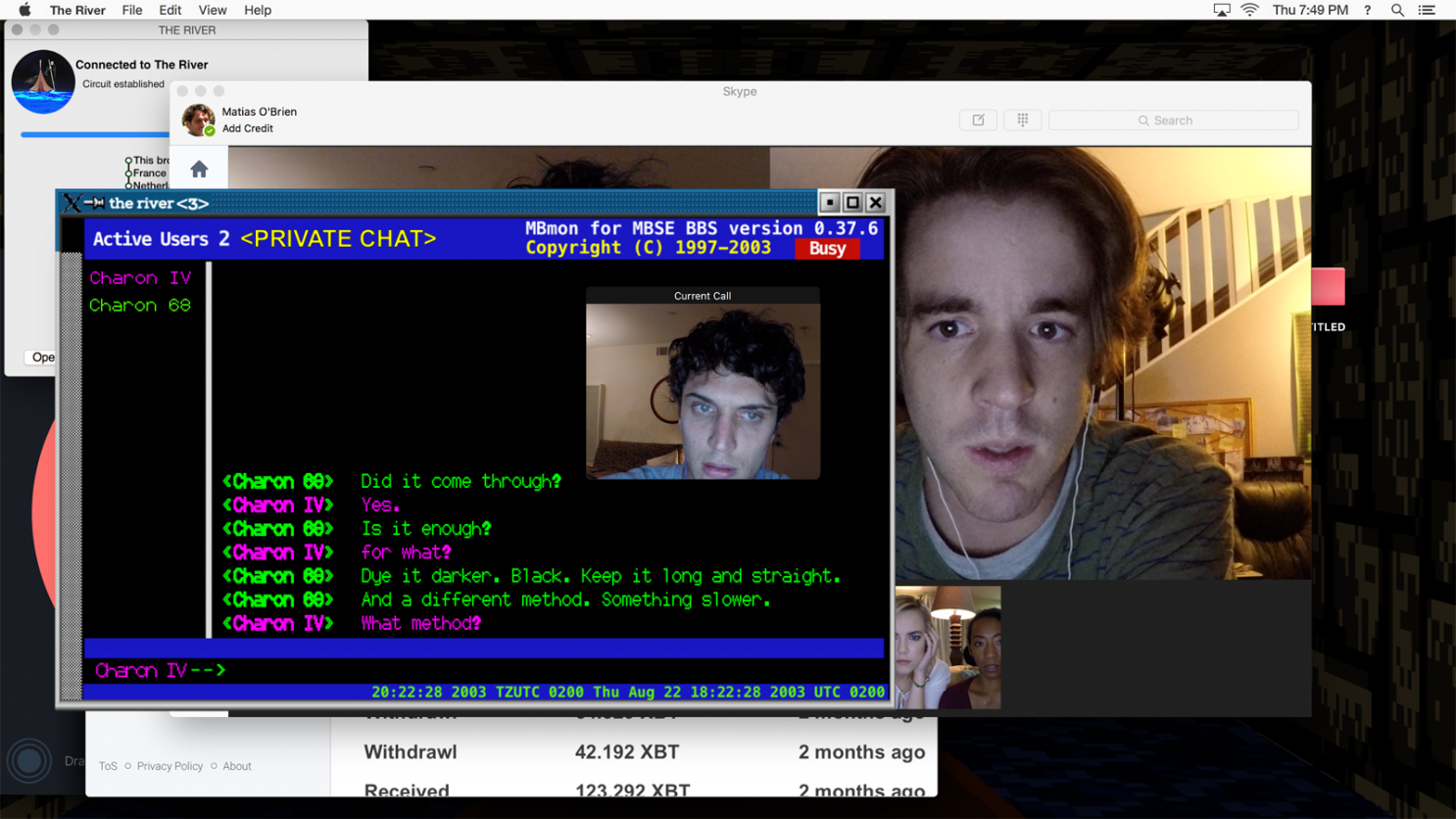

With grisly revenge exacted on each teen, Gabriadze created a template for Stephen Susco’s 2018 follow-up, Unfriended: Dark Web. In the later film, a group of comparatively older––though no less web-savvy––friends congregate over Skype for their weekly game night, but programmer Matias (Colin Woodell) is calling from a new MacBook, which he filched from an internet café’s lost and found. The remembered tabs, social media sign-ins and the harddrive denote a discomfiting affiliation with the dark web of the title, and the friends are dragged into a byzantinian plot of masked identities, cryptocurrency and stomach-churning torture porn that saddles each protagonist with a fate similar to those in the previous film.

Both films capture the tangible sensation of clicking across one’s screen and of the distraction inherent to powering on and logging in, with the desktop activities providing a fascinatingly fleeting mise-en-scene. But it’s the characters’ handily plugged-in lexicon, a cavalcade of words and phrases so utterly inextricable from the internet that an imagined private and safe realm within the current incarnation of the public web feels all the more out of reach. As billie227 begins dropping hints at their identity, the high schoolers start throwing out terms like “troll” and “glitch” as if they could alleviate the fear on their faces. The total lack of control is crystallized with the blown out, pixelated images and the ways in which the image occasionally freezes. Mundane instances of our devices failing us yield deadly results, where one’s death could be avoided if only someone on the other side of the screen could have told them to “look out.” Instead, the connecting capabilities of computers are yanked from the victims, and they are made mere spectators to their friends’ deaths.

Unfriended functions as a teen ghost story set loose across Facebook Messenger, whereas Unfriended: Dark Web’s central group brings forth what others may have considered simply to be an urban myth. Matias must fend off numerous, creepily anonymous (as visualized by their sparse social media accounts) interlopers to both his friends’ game night and “his” personal desktop, all of whom are presumably agents of the dark web of the title. Similar to its predecessor, Dark Web outlines a certain nigh-ridiculousness that comes with our efforts to safely compartmentalize the internet, so that even when Matias and co. correctly deduce the origins of their villainous harassment, they’re still rendered powerless. One particularly unsettling sequence sees the shadowy organization piecing together a police call from friend AJ’s combative YouTube videos to effectively swat him. This murderous method echoes the way in which Moloch disposes of his otherwise flappable underlings in “I Robot, You Jane”; after Dave refuses to go after Buffy, Moloch’s spectre electronically drafts his “suicide note” before he is hanged by Fritz. The way in which these perpetrators so effortlessly circumvent all defenses demonstrates the ways in which our online profiles are never truly in our sole possession.

“I Robot, You Jane,” Pulse and the first Unfriended logically follow one another in their embrace of a supernatural force present within the mainframe, but Dark Web positions itself adjacently, rather than atop its quasi-predecessors. For one, Dark Web, despite its truly horrifying spiral from bad to worse, is not predicated on the supernatural; these dark web villains may manifest themselves in a manner usually attributed to ghosts (most notably, their sudden appearance and disappearance), but they are flesh and blood human beings nonetheless. While “realism” is not the end goal of the film, its forgoing of the supernatural––which can provide something of a safety net of indisputable fiction, no matter how flat-out scary things can get––results in an even more nihilistic vision than Pulse or Unfriended. Dark Web proves how the kind of horror that punctuated the aforementioned films can conversely originate from more earthbound circumstances, and this is what makes it perhaps the most prescient, if not just the scariest of this grouping. The unquantifiable arcs of Pulse and Unfriended are repurposed for Dark Web’s unnerving insinuation: this cycle of web-bound deceit and torture is fun for its architects, the vastness of the internet exploited for a game of cruel victimization.

Dark Web not slotting perfectly within this informal chronology is a resoundingly appropriate shift in the manner in which the internet is employed as a scare tactic. As the films before it have each respectively pushed up against their own narrative boundaries in how they incorporate the web, it was only a matter of time before the supernatural strictures gave way and spilled over into “real life.” Still, each work manages to retain technological tokens of our own everyday, no matter how hyperbolically (Buffy, Unfriended) or subtly (Pulse) they may be presented. Across these films, a motley crew of programmers, novices, and everything in between is assembled, and more often than not, all are subject to the same fate. The senselessness on display isn’t gratuitous, but a hyperreal working model of the immovable conditions of our own online selves. The success of these works can be attributed to the still-prevalent human element in each, with each director allowing for expressions of shock and bewilderment to register, potent moments of realization in which online safety measures prove themselves null in the face of a digital abyss which spans into an infinite unknown.